It does not matter today anymore whether I was fired as a political refugee or as a citizen of Czechoslovakia. I think both ways are in fact criminal.

Download image

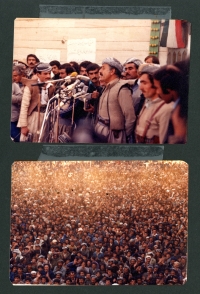

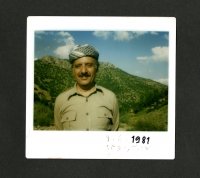

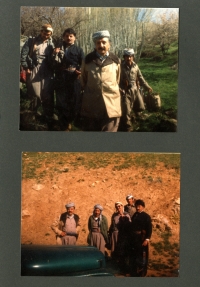

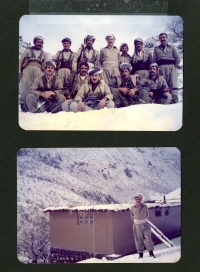

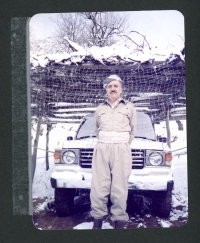

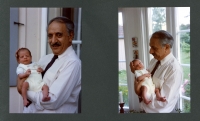

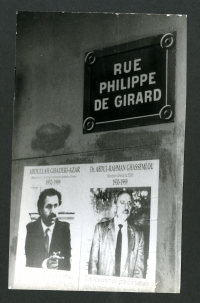

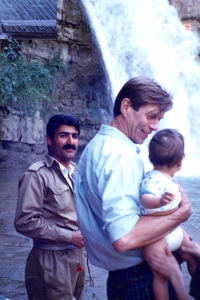

Mina Norlin was born on April 19, 1953 to a czech mother Helena Krulichová and father Abdul Rahman Gassemlou, an Iranian Kurd. In the autumn of the same year, Mina as a six months old baby was transferred to Iran, where her father worked in the resistance against the Shah. Over the following months, the family grew by Mina’s sister Hiva. At the end of 1957, Abdul Rahman Gassemlou was sentenced to death. He therefore decided to leave the country with his wife and children and applied for asylum in Czechoslovakia. Thanks to a quick travel with foreign passports, the family lived in Prague under false names until 1968. So, Mina learned her real surname at the age of fifteen after receiving an ID card for foreigners with permanent residence. In 1973 her father was elected as the chairman of the Kurdish Democratic Party in exile. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, he traveled abroad and engaged in the Kurdish national movement. However, he tried to keep his children out of the way in order to keep them safe. The turning point occurred in 1976 when the Czechoslovak authorities refused to extend the residence permit for the whole family. Mina and Híva applied for asylum in Sweden. Parents moved to Paris, where Gassemlou received a teaching contract at the Sorbonne University. After several years in Stockholm, Mina got married, set up a family, and studied architecture. On July 13, 1989, Abdul Rahman Gassemlou and his colleagues were murdered in a meeting in Vienna with representatives of the Iranian party. In the shadow of this family tragedy, Mina watched the fall of the Iron Curtain and when she was given the opportunity to move back to Prague in 1992, she did not hesitate.