I was born as a German and I’ll die as a German

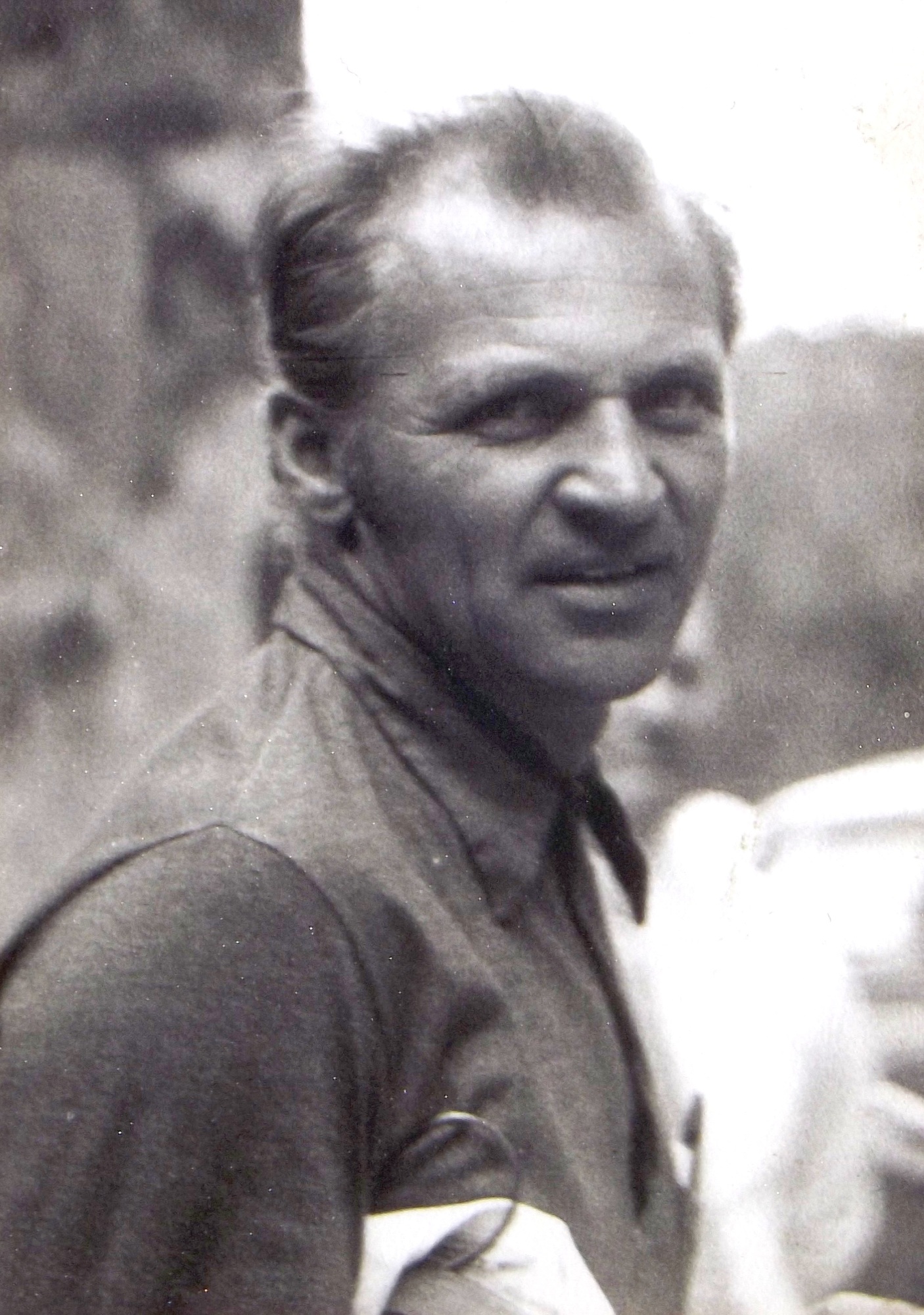

Hartmut Moškoř was born in 1929 the youngest son of Wilhelm and Marie Moschkorz. He grew up at the family estate in Staříč near Frýdek-Místek. They represented a traditional German family from the Czechoslovak borderlands. His father was actively engaged in Nazi organizations and held the post of deputy mayor in Staříč in the times of WWII. As an influential man, he tried to help his fellow Czech citizens and he often encountered informing and collaboration by Czechs. In March, 1945, he was murdered in his house by unknown offenders. After the liberation, Hartmut’s mother, together with his younger brother and his sisters, was placed in an internment camp. She was beaten to death by the members of the militia on May 6, 1945. Hartmut was sent to forced labor in the mines. Afterwards, he worked in agriculture. He faced charges of arson but was acquitted by court. In 1953, he regained his Czechoslovak citizenship and changed his family name to Moškoř. He worked in industrial production and became a mechanical locksmith and an inventor. He is the author of three patents and numerous improvement proposals. Since the 1960s, he’s been engaged in yachting. He played a part in the establishment of the TJ Palkovice Yacht Club at the Olešná Dam. Since 1989, he’s been in retirement. In 2007, he sponsored the publishing of his memoirs “Kdo seje vítr... sklízí bouři (Svědectví o tom, jak jsme žili)” (Who Saws the Wind… Reaps the Storm – a Testimony About our Lives).