Life in the land of two truths and silence

Download image

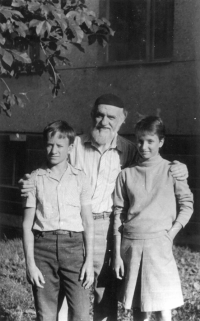

Vera Meier was born Vera Hoszowski on 27 July 1973 in Lviv, which was then part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and where she spent her childhood. Her paternal ancestors came from an old Polish noble family, the Hoszowskis, but lost their property and social status sometime during the 19th or 20th century. There is no knowledge of how it happened; the Hoszowski family did not discuss things whether in line with the strict patriarchy that literally governed family life or out of caution: everyone was supposed to be equal in socialist countries, and if you were not you should at least keep quiet about it. The mother’s side of the family came from the city of Poltava in central/eastern Ukraine. As teachers, her grandmother’s family survived the artificially induced famine of the 1930s during which an estimated four million people died. The grandfather came from a region beyond the Urals and arrived in Ukraine during World War II as a civil engineer. Both grandparents were communist party members and believed in the ideology promoted by the state. So when Vera’s father - the son of an ancient noble family of Greek Catholic creed - was to marry a communist daughter, it caused an uproar. Still, they married and the family settled in Lviv where Vera was born in 1973, followed by her brother Volodymyr. Vera remembers her childhood as a time of secretly celebrating family traditions and church holidays when, if a neighbour happened to ring the doorbell during Easter celebrations, they were told it was a birthday party. What if he was a secret police collaborator? She also describes her childhood as a time full of parties thrown by her parents when the children were sent to bed early but still listened by the door to political jokes told over wine. And also as a time rife with school parties praising the building of a brighter tomorrow set against the background of a stark food shortage - the family survived the winters in the 1980s thanks to the potato and sauerkraut supplies in the cellar. The Chernobyl nuclear power plant disaster on 26 April 1986 could be seen as a kind of harbinger of the end of socialist regimes. A few days after the disaster, Vera merrily walked to the May Day parade with her grandpa. But why were there so many sprinkler trucks on the streets and why, as a thirteen-year-old child, she was constantly vomiting? There was no way to link that to the disaster at the time - the regime kept the explosion under wraps as long as it could, that is, until the information leaked from the West. A few years later - when the socialist regime finally collapsed in Ukraine - Vera went to study Slavic Studies at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in Prague, where she was living at the time of the filming in 2025.