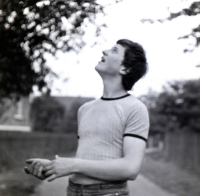

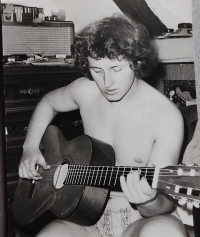

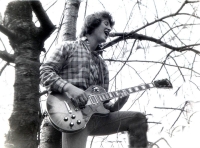

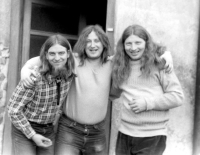

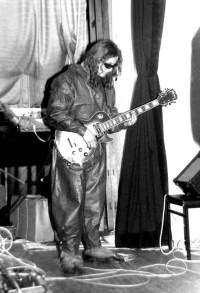

Rock music was a symbol of our freedom

Download image

Leoš Mayer was born on 2 June 1964 in Liberec, but lived with his parents in nearby Hrádek nad Nisou. In 1977, he saw the propaganda documentary Attack on Culture, which made the opposite impression to that intended, and he wanted to learn more about the people the regime was attacking in the documentary. In 1979, he was a founding member of HRC (Hrádek Rock Circus), where he played guitar. After graduating from high school and completing his compulsory military service, he began working on the railway line as a locksmith. During this time, he met Jiří Fajmon, who made a great impression on him. When he became more familiar with his fate, he decided to become more active against the communist regime. In 1987, he and his friends founded the underground group UKD (Destined for Demolition) and began to transcribe and distribute samizdat literature. In addition, he was actively involved in writing his own magazine, Nákup, together with Jiří Fajmon. In February 1988, he and his wife signed Charter 77 in the apartment of Petr Uhl and Anna Šabatová. From August 1988, he participated in anti-regime demonstrations. During Palach Week in January 1989, he and his wife, Michaela, went to Všetaty. He experienced the Velvet Revolution in Liberec, and after the fall of the regime, he retreated into seclusion. At the time of filming (2024), he lived in Hrádek nad Nisou.