Treatment was part of the punishment. If someone didn’t like you, you got thirty drops of Neuleptil and were knocked out for a week

Download image

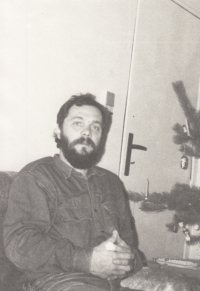

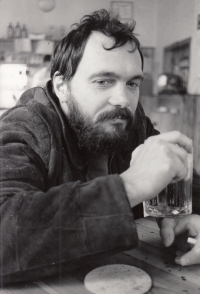

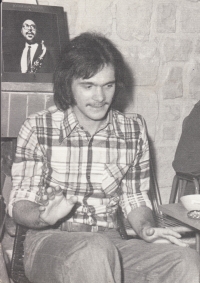

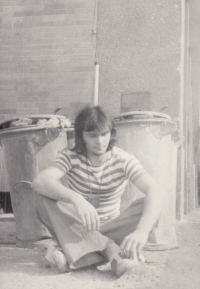

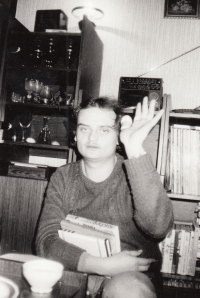

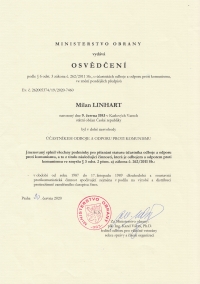

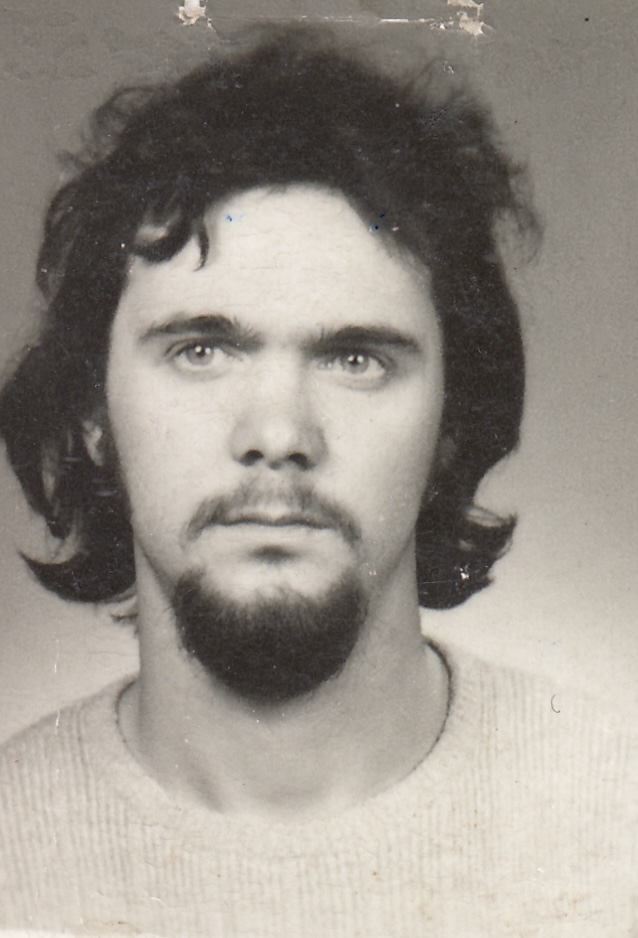

Milan Linhart was born on 9 June 1953 in Karlovy Vary, the second of three brothers in the family of František Linhart and Berta Linhartová. His father worked as a bank clerk, his mother originally as a porcelain painter, later, when her sons grew up, she worked in administration and as a dietary nurse in a hospital. He grew up in a culturally stimulating environment, shaped by his father’s critical attitude towards the communist regime. A crucial turning point in his adolescence was 1968, when he experienced the occupation of Czechoslovakia and its violent consequences in Prague and Karlovy Vary. His father, who was a member of the Club of Committed Non-Partisans (KAN), was fired from his job at the beginning of normalisation. In 1968, Milan started his apprenticeship as a refrigeration mechanic in Častolovice, and was often in Prague in the environment of alternative youth and underground culture. Due to conflicts with a repressive boarding school tutor, he was expelled from the apprenticeship. He worked as an orderly at the General University Hospital, attended concerts of banned bands and gradually the repressive state forces became interested in him. In 1972, he was sentenced to an unconditional ten-month prison term for drugs, distribution of banned literature and politically compromising material. After serving his sentence, he was placed by court order in a psychiatric hospital in Dobřany, where he spent eight months in an environment that was part of the repressive apparatus of the normalization regime. After his release, he lived in Chodov, where he worked in the labour professions, founded a jazz club and studied at the Secondary Technical School (SPŠ) of Mechanical Engineering. In 1979 he signed Charter 77 and in the 1980s he was actively involved in dissident activities, spreading samizdat and organizing unofficial meetings. In November 1989, he participated in the founding of the Civic Forum in Karlovy Vary, but later withdrew from politics and devoted himself to working in the family business. At the time of the interview in 2025, he lived in Mezirolí near Karlovy Vary.