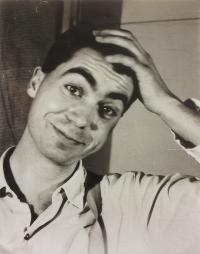

Live for joy

Download image

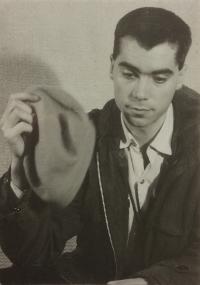

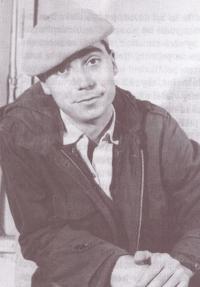

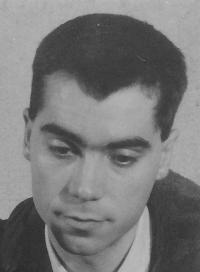

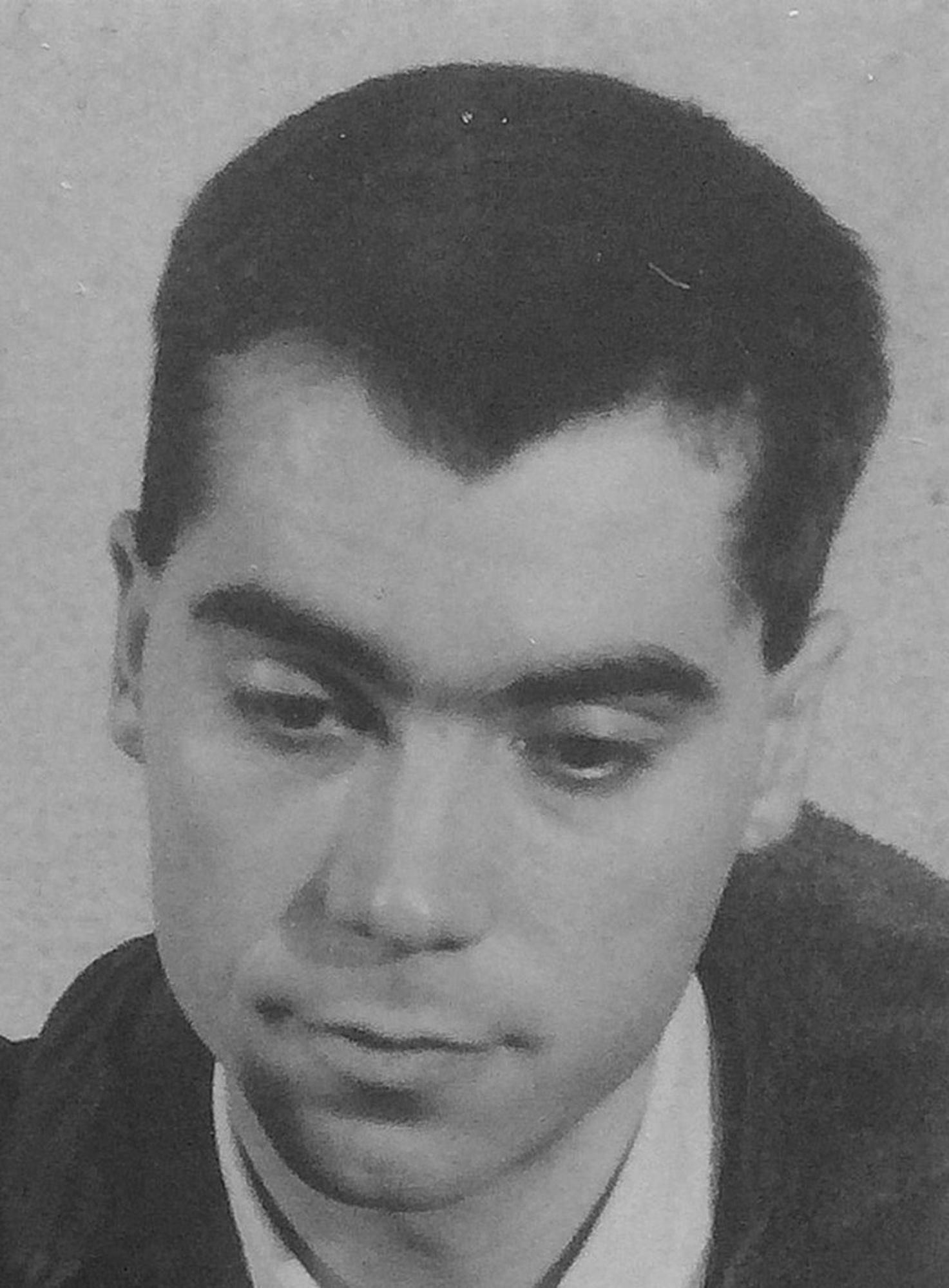

Pavel Lagner was born in 1966 in Břevnov, Prague. His father was a carpenter and his mother worked as a nurse. He has an older brother. While he was growing up, his family was religious and had an anti-communist attitude. His views did not cause him problems in elementary school or the Johannes Kepler Grammar School. After graduating he wanted to study visual art but neither AVU nor UMPRUM accepted such young applicants. He tried enrolling in a programme at the Faculty of Education but was rejected. The main problem for him was the two-year military service which he did not want to go through. He started working then, and truly experienced the reality of socialism. A year later he was actually accepted at the Faculty of Education but by then he had already been developing an interest in theatre. Two years later he was accepted at DAMU. During his studies he witnessed the Velvet Revolution and organised student events with other students. Nowadays he performs at the Kašpar theatre and works as a curator at the Václav Špála Gallery.