The communists hurt us a lot. But thanks to them, I met my wife

Download image

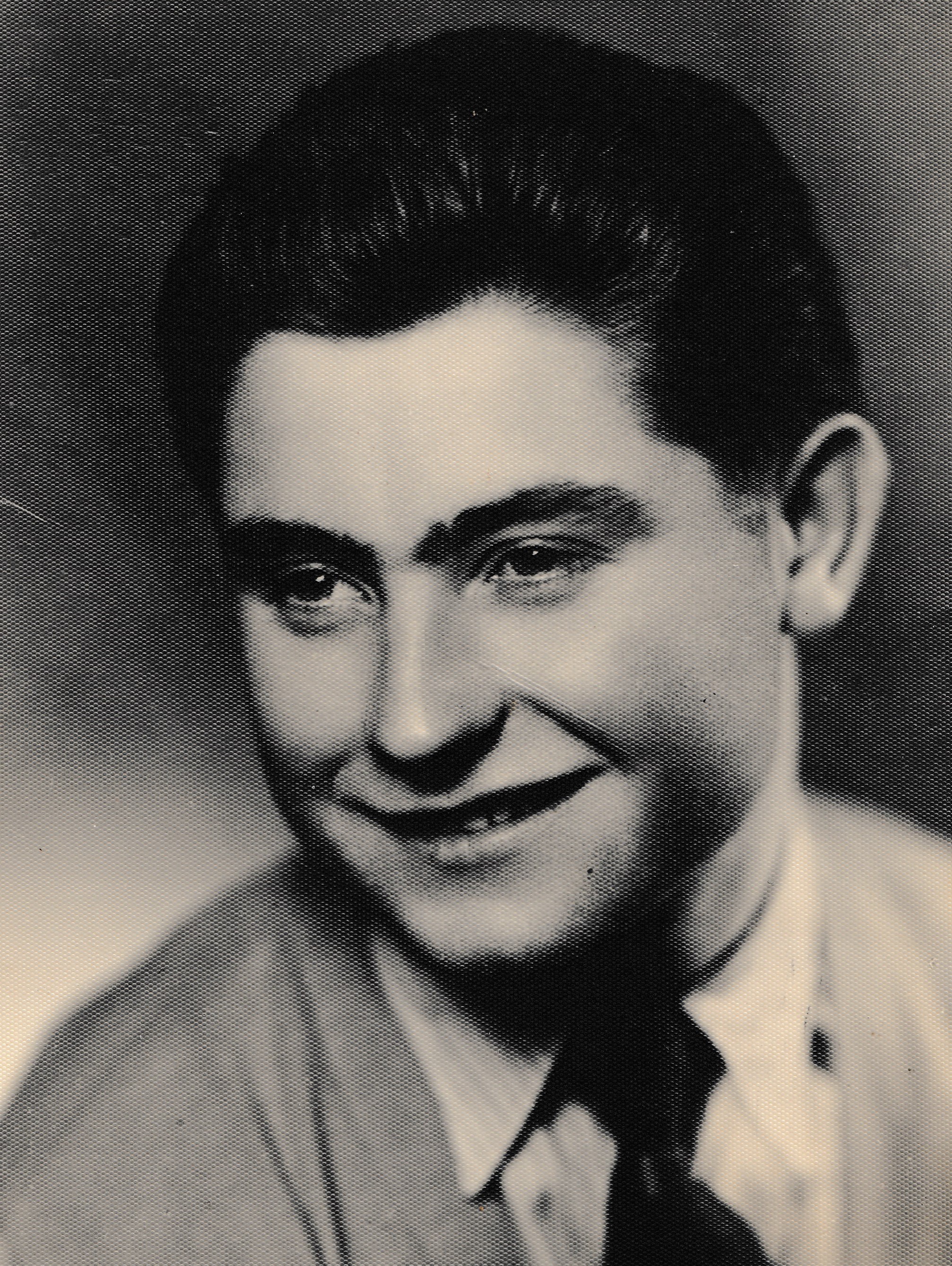

Karel Krušina was born on September 21, 1938, to Gustav and Aloisie Krušina in Koloděje near Prague. Two days after his son’s birth, his father had to join the army because general mobilization had been declared. The family ran a bus transport business, which his father continued to operate after his return from mobilization until 1943, when the Nazi authorities revoked his license for refusing their offer to transport ammunition. The Krušina family lost their livelihood and moved to the mother’s parents in Stvolová in the Svitavy region on the border between the Protectorate and the Sudetenland, where they remained until the end of the war. Shortly after the war, father Gustav Krušina died and the mother decided to stay with her sons at her parents’ house. After some time, however, she moved back to Koloděje with her children. She applied for the return of the bus transport license, which she eventually achieved after a long battle with the authorities, and started her own business. The company began to prosper, and Aloisie Krušinová wanted to build a new house for her family, including garages for buses. However, 1948 came and the Communists took power. The unfinished house, garages, transport business, and even the farm inherited from her parents in Stvolová were nationalized. She managed to save at least the house in Stvolová, where she moved back with her sons. Their mother tried to restore the farm and sowed the fields. Soon, however, a unified agricultural cooperative was established in the village, and officials asked Aloisie Krušinová to join it. She refused, and as a result, the whole family lost three months’ worth of food stamps. Shortly thereafter, in 1953, a currency reform took place and the family lost all of their savings, which were intended to pay for their younger son Karel’s studies at an automobile training school in Mladá Boleslav. He had to leave school immediately and start working to help his mother support the family. He started working and training at the Sandrik company in Moravská Třebová, where he remained until his retirement. With the prospect of a better life, the witness joined the Communist Party in 1960. However, because of his disagreement with the invasion of the occupying forces in 1968, he was expelled from the party by officials and was also bullied at work because of this. However, he transferred to another department and the situation calmed down. In 1989, he briefly became involved in the activities of the Civic Forum in Moravská Třebová, but soon withdrew from politics. Karel Krušina has two sons. In 2025, he lived in Moravská Třebová in a house he built himself in 1968.