Appreciate, what you got; freedom of speech, of travel, as we had none of that

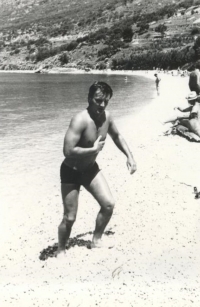

Download image

Vojtěch Kříž was born on 2 April, 1944 in Příbram. He lived with his parents in Radětice and went to school in Stěžov and later to Milín. He apprenticed a mining locksmith. At the age of eighteen he began working in the mines and liked his job. During basic military service the witness was sent to serve at the tank troops in Tábor. He graduated from the sub-officer school. In 1966 he began working at the shaft 16. Following the Warsaw Pact armies occupation on 21 August, 1968 he participated in a weekly strike together with his colleagues. Apparently the miners were just maintaining the mining equipment and secured the operation of the pumps, so that the mined did not get flooded, but otherwise did not work at all. He remembered the chaos the occupation brought, and people purchasing all kinds of supplies; there were labels saying „Not a gram of uranium more” and the occupants, who replied to explanations and questions only by single words referring to order and contra revolution. The occupation meant the end of all hopes he had for the future of our country. The only memory left, in his words, was a lovely meeting with Alexander Dubček and Josef Smrkovský with the miners. In 1969 he married and began constructing the family house with help of his work mates. He works in uranium mine for eleven years. It took ten months for him to recover from a heavy injury, which he survived only by a miracle. After that he could only work on the surface. He had a son and has two grandsons. Currently he works in the Mining Museun in Březové Hory.