I walked on across the craters

Download image

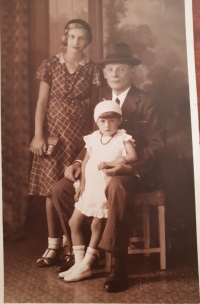

Eliška Krejčová was born on 11 September 1927 in Kralupy nad Vltavou. Her father, Václav Fürst, worked as a painter and varnisher, her mother was a housewife, but had previously trained as a seamstress. As a child, the memoirist and her two older brothers went to friends in the Sudetenland to learn German. From childhood she played table tennis. She grew up during the Second World War. At that time she commuted to Prague to attend business school, which she completed before the end of the war. In March 1945, Eliška Krejčová experienced the bombing of Kralupy nad Vltavou, during which their house was destroyed. Her father was later forced to sell the plot to the town. After the war, she started playing table tennis at a professional level in Sparta in Prague. In 1947 she even travelled to the World Championships in Paris. After the onset of communism, she married Oldřich Krejčí in 1949. She continued to represent Czechoslovakia at various international tournaments in the Eastern Bloc. For the opportunity to participate in tournaments in West Germany in the 1950s, she signed a cooperation with State Security. At the same time, she worked at the Kompresory ČKD company. At the end of the fifties she finished her career as a professional table tennis player and started working in the spare parts warehouse of ČSAD Kralupy nad Vltavou, where she worked until the eighties. After the Velvet Revolution, she tried to acquire the plot of her bombed-out house, but eventually abandoned the idea. In 2024 she was living in a nursing home in Kralupy nad Vltavou.