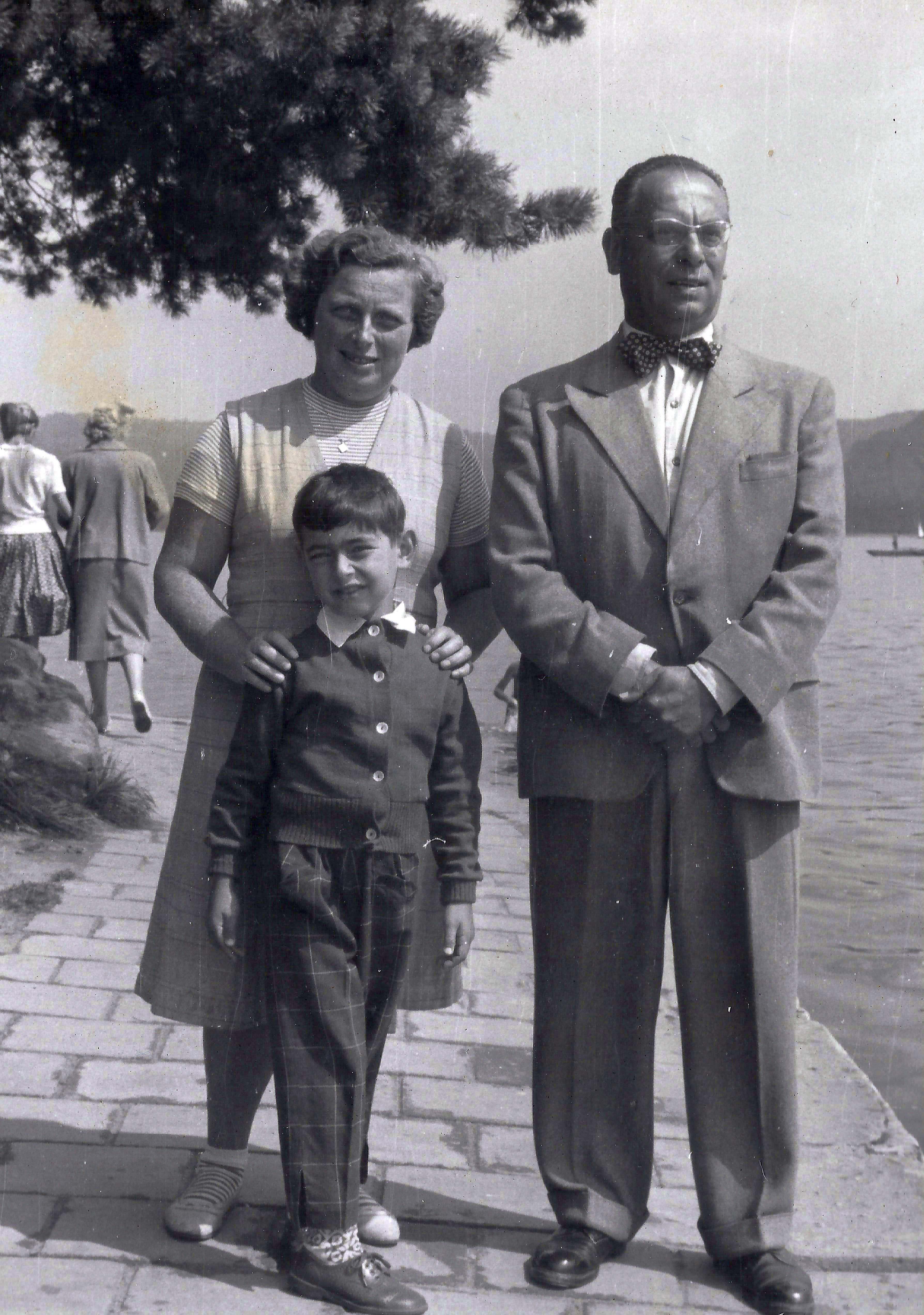

Jewish identity is part of me

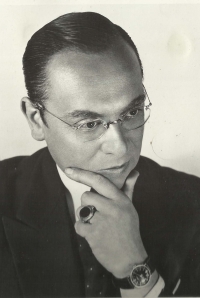

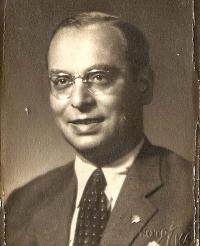

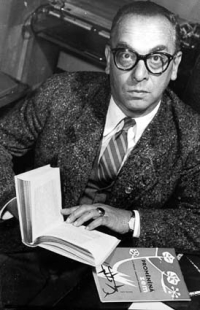

Download image

Tomáš Kraus comes from a Jewish family, his parents are Holocaust survivors. His father František R. Kraus was a publicist and writer. His mother, Alice Kraus, née Flusser, came from a German-speaking family from Teplice and lost all her relatives during the Holocaust. Their son Tomáš was born on 19 March 1954 in Prague. He grew up in Prague’s Žižkov district and graduated from the grammar school on Sladkovského náměstí. From early childhood he was involved together with his parents in the Prague Jewish community, especially during informal meetings and holidays. After an unsuccessful attempt to gain admission to FAMU (Film and TV School of Academy of Performing Arts in Prague), he started studying at the Faculty of Law of Charles University in 1975. During his studies at the law school he worked with the Jazz Section. After graduation he joined the foreign department of Supraphon, where he was mainly involved in the export of Czech classical music abroad. From 1976, he was followed by the State Secret Police (StB) as part of the so-called “Spider” operation, aimed at tracking Jews. In autumn 1977, the Police contacted him for the first time. He met with the officers every few months until 1988. At first he was kept as a confidant, and in 1984 the State Secret Police pushed him to sign a pledge of secret cooperation. Tomáš Kraus states that he did so unknowingly, believing that he was signing a confidentiality agreement. In 1988, the State Secret Police terminated this cooperation because he did not bring any relevant information. From 1985 he worked at the Artcentrum Company, and in 1991 he became secretary of the Federation of Jewish Communities. In his position, he was mainly involved in efforts to obtain compensation for Czech Holocaust victims from Germany and restitution of Jewish property. Today, he serves as an advisor to the Federation of Jewish Communities and is the director of the Terezín Initiative Institute.