The longing for family, friends and theater brought him back from democracy to totalitarianism

Download image

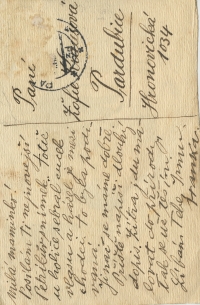

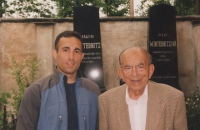

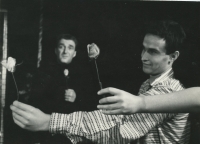

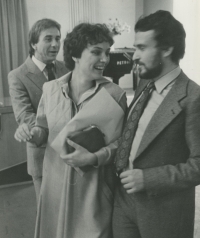

Josef Kraus was born on February 3, 1941 in Pardubice. His father Jiří Kraus came from a Jewish family and ran a cardboard box factory at the Pardubice chateau. His mother was the daughter of the butcher Wurst from Pardubice. His father did not bear the burden of anti-Jewish regulations, and in September 1942, three months before the transports to Terezín, he took his own life at the age of 39. Josef Kraus’ mother got married for the second time after the war, she married a farmer from Vysočina, who was being persecuted for a change in the 1950s due to her reluctance to join a collective farm. Josef Kraus was expelled from the second year of the Secondary Agricultural School in Hořice for cadres reasons (a file with information about one´s class background, one´s views and ideological attitudes) . He joined the Semtín factory as a worker, where he, for the first time, became one of the actors in the local amateur theater. Over time, their ensemble became a professional ensemble, but the authorities dissolved it after three years after problems with unwanted satire. For several seasons, Josef Kraus and two colleagues moved to Ostrava, where he performed alongside Jan Kačer and Evžen Němec until the ensemble left for the Drama Club in Prague. Josef Kraus returned to Pardubice, got married and had their first daughter Renata. In August 1968 he emigrated via Romania to Switzerland and later to Germany. After less than three years, he returned from the exile to Czechoslovakia to his family, to which his second daughter, Ester, joined in 1972. After returning from emigration, Josef Kraus had trouble finding a good job, but eventually worked in the Magnet mail order store in Pardubice. He got divorced and remarried, having a second wife, Eva. In 1991, he acquired his grandfather Wurst’s butcher’s shop in restitution, and he and his family tried to restore it. The established company was sold in 2011. For more than twenty years, Josef Kraus has been a key member of the Jewish cemetery in Pardubice. In 2021 he lived with his wife Eva in Dukla, Pardubice.