“Not to provoke, simply to live with that system, but to be proud of it, to cultivate the Hungarian language, to cultivate Hungarian culture, not to forget who we are, and so on.”

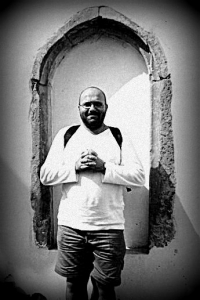

The memorial, Ľudovít Kossár was born on May 5, 1965, at five o’clock in the morning, under very unflattering conditions of the flood, in Komárno. Due to the evacuation, after his birth, he was taken to Bratislava with his whole family. Ľudovít mother’s name was Kokošová as a single woman and she came from a Slovak-Hungarian couple. His father, Štefan Kossár, was of hungarian nationality and his family’s roots go back to the fifteenth century. Ľudovít is from six siblings, three of them are from his mother’s second marriage. As he attended just hungarian institutions, he learned the slovak language only thanks to exchange stays between the north and south of Slovakia, during which he visited, for example, Duchonka or Banská Bystrica. During his childhood, he has never expressively felt the pressure of the Slovak part, because of his hungarian nationality. The first signs of Slovak chauvinism were discovered in the age of puberty, in the years 1974-1975. The memorial as a small child has never attended kindergarten. For the first time he attended an educational institution as far as the Hungarian primary school in Komárno, where he also successfully graduated from grammar school. Later he decided for the Faculty of Arts of Comenius University in Bratislava, for the department dealing with historiography. He was accepted for the second time in 1984, due to lack of space. At the beginning, he registered two language problems, the teaching of Slovak and Hungarian historiography, which were different, but due to random checks they had to deal with both. During his university studies, Ľudovít also met with teachers who described themselves as racists towards Hungarians. Before graduating from university, in 1989 he did not miss the writing of a diploma work on the topic, Freemasonry. In 1990, he successfully graduated from university. After college, he worked as an editor for the daily NAP. Later, in 1994, he became the deputy director of the Slovak Film Institute in Bratislava, where he first experienced discrimination and due to his Hungarian nationality, could not become the director of the institute. Approximately at three-year intervals, jobs followed as deputy director of the cultural house in Pezinok, the position of director of the area Štrkovecké lake and the interesting position, the director of the publishing house, Kalligram. In 2010, he started a business in gastronomy. Ľudovít Kossár has publicly admitted to homosexuality. His current relationship lasts fifteen years. Public admission during the communist era was very demanding, because he could be prosecuted or taken to treatment. He considered himself a minority in the minority because he was of hungarian nationality and had an affection for the same sex. Despite the fact that there was a woman in his life, he could not stand it and he officially admitted only after the revolution. The memorial lives in Bratislava for 37 years, so because of this he is considered a Bratislava citizen with Hungarian roots. Nevertheless, he still has a large part of his family in Hungary, so frequent visits are a matter of course.