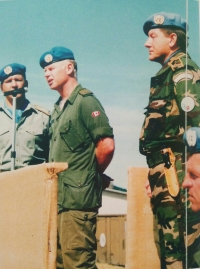

War and Peace - life struggles of the first Slovak commander in UN missions.

Download image

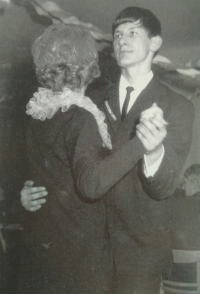

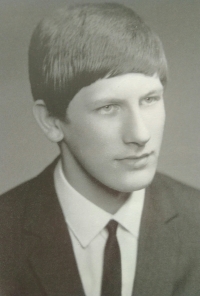

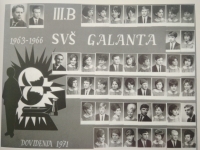

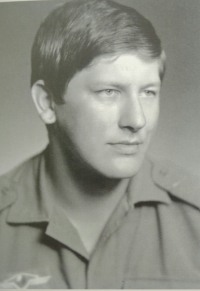

Ľubomír Kolenčík, born on February 23, 1948 in Galanta, decided to pursue a military (and sports) career in high school. He graduated from the engineer school in Bratislava and later from the military academy in Brno. Most of his military life was connected with the engineer detachments in Seredi, until he joined the Municipal Military Administration in Bratislava at the end of the 1980s at the rank of colonel. In 1993, he was selected as the first commander of the Slovak Engineer Battalion in the UNPROFOR peacekeeping mission during the civil wars in the former Yugoslavia, where he spent a total of four six-month periods. Shortly after his return to Slovakia, he retired to civilian life in 1995 and since the late 1990s has developed a successful career in the field of systems management.