The Soviet soldiers asked: did he die already?

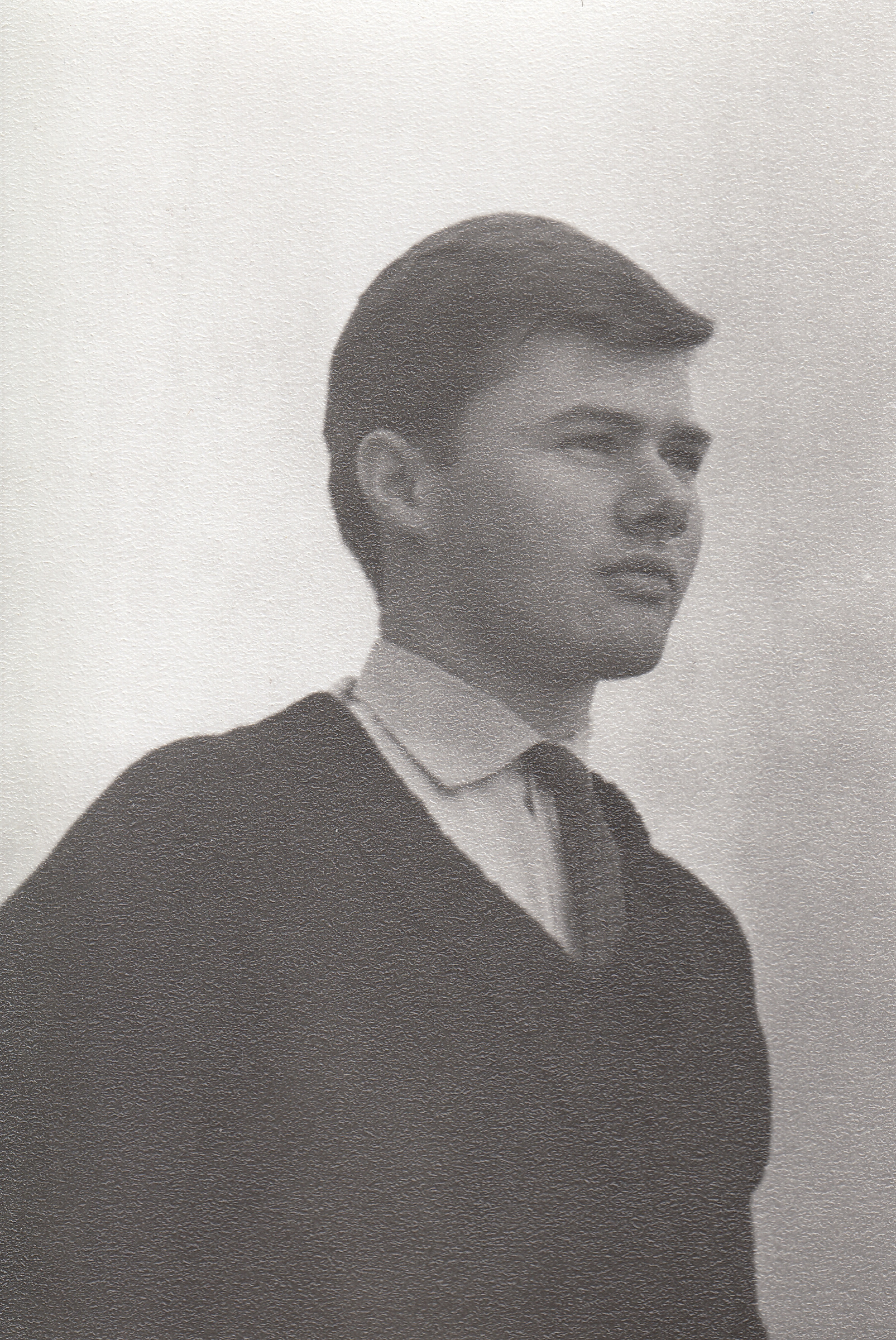

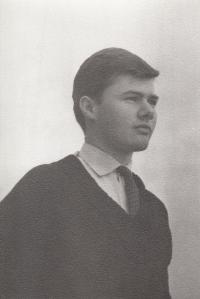

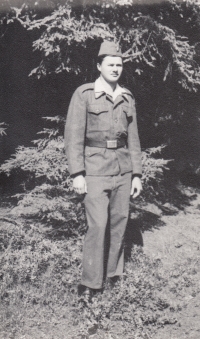

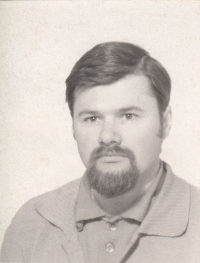

Jiří Kolda was born on 24 March 1942 in Prostějov. In 1947 he and his parents moved to Prague. His father was a physician who refused to join the Communist Party. His mother was the daughter of a butcher. Because of this family background, Jiří had trouble with admission to university. Eventually, he graduated from a textile engineering school in Liberec. Then he got a job at the Ministry of Transport. In the night from the 24th to the 25th August 1968, at the time of the Warsaw Pact invasion to Czechoslovakia, he had a night shift in the control room. The Ministry was overrun by the Soviet troops who were searching for weapons. By mischance one of the soldiers opened fire against Jiří. Then the soldiers transported him to the Stromovka park where they left him for several hours without medical care. Only when his colleagues from the Ministry started looking for him the next morning, he got treated in a field hospital and the Soviets allowed for a Czech ambulance to come and pick him up. He sustained severe injuries; one of the bullets missed his heart by one centimeter. He has suffered from the effects of the delayed medical care for the rest of his life.