If the Russians had liberated Terezin a fortnight later, I wouldn’t be here.

Download image

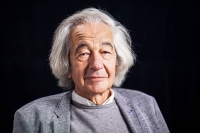

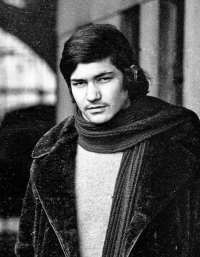

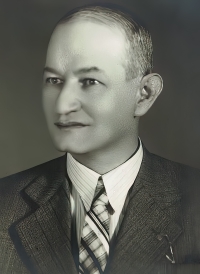

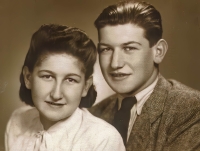

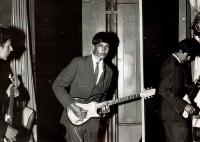

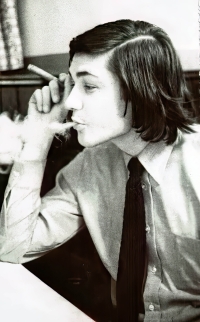

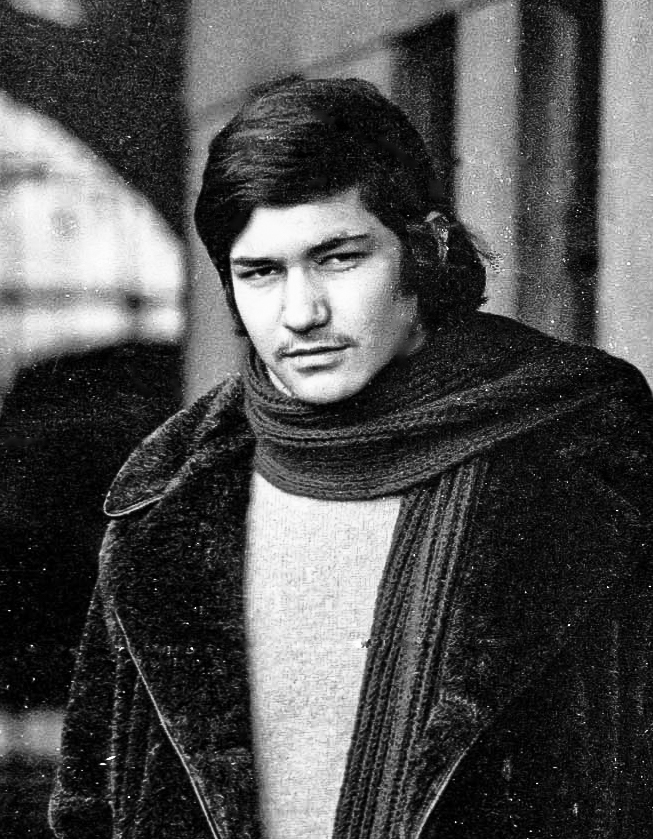

A descendant of Jews from České Budějovice, Jiří Kende was born on 11 August 1951 in Prague to Viktor and Irena Kende, who survived imprisonment in the Terezín ghetto. One of his grandfathers, Jiří Stadler, perished in Terezín, while the other three grandparents, Vilém and Valerie Kende and Alžběta Stadlerová, were murdered in the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz. At the end of the war, his mother’s brother Rudolf Stadler, who was the founder of Klepy, a unique magazine for Jewish youth in the Protectorate, was also killed. Jiří spent his childhood with his older sister Hana in a part of Prague called Little Berlin, where people who had lost everything in the war moved into the apartments vacated by the Germans. While studying at secondary school, he took advantage of the relaxed political situation in the late 1960s. He went to visit his uncle in the United States, where he was later caught up in news of the invasion by Warsaw Pact troops. While his sister remained permanently in England, Jiří returned to Prague in 1969. He finished his studies and began to work. In 1973 he met his future wife Gabriele, who had come to Prague from the German Democratic Republic on a sightseeing trip with a group of female students. It didn’t take long for him to get married and follow her to West Berlin with his emigration passport. There he began to study economics, earning extra money to pay for his studies as a medical assistant in the hospital at night. Before retiring, he worked as the director general of the university library of the Freie Universität in Berlin. In 2021 he was living in Berlin with his second wife Petra.