Only living outside Czechoslovakia cleared him of the sign of the class enemy

Download image

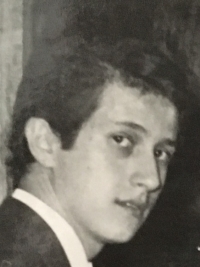

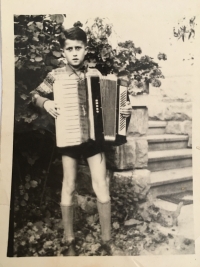

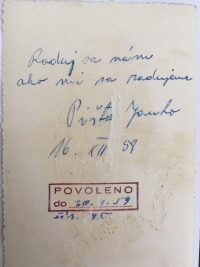

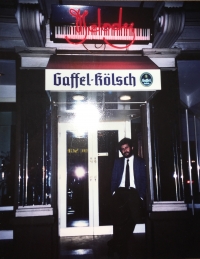

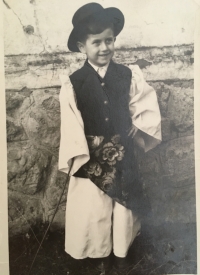

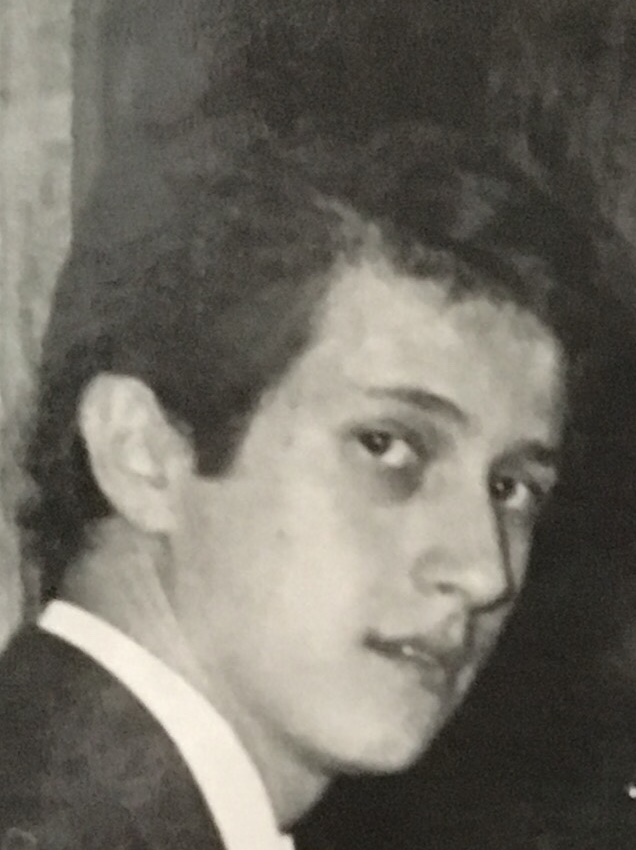

Stefan Katona was born on January 14 in 1947 in Sahy into a family of a great landowner of a Hungarian-Jewish origin. In the early 50s, the whole property of the family was expropriated and the father had to work manually. Shortly afterwards, he became an administrator of state property at Sumava, which was expropriated after deported Germans. A few months after the family moved into Sumava, his father was charged with the sabotage of Socialist economy and in a political trial in 1955 sentenced to 8 years in uranium mines in Jachymov. Stefan and his mother moved back to Sahy. His mother worked as a shop assistant and she barely managed to provide for the family. The boy was interested in music since childhood and as a gifted student, he dreamed of studying at the conservatory in Bratislava. Due to his bad “political profile,” he could not attend a high school with high school-leaving examination enabling entrance to university and he had to continue on a vocational school. However, due to chance and his courage, Stefan managed to switch to secondary technical school in Zvolen and later in Bratislava. Together with his 16-year-old brother, he illegally travelled to Israel, for which he was found guilty in absence. Mother followed him a year later. Their father emigrated to Germany after the Soviet invasion in august 1968. Stefan moved there in 1971 with his wife, he played in various bands after work, in 1983 he opened jazz club Melody Piano Bar in Koln, which remained a legendary place for local jazz fans for next 30 years. After 1989, he visited places of his childhood.