One of the Brave Ten

Download image

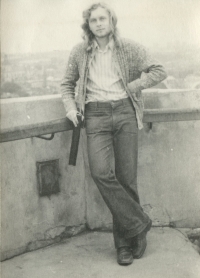

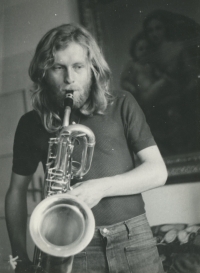

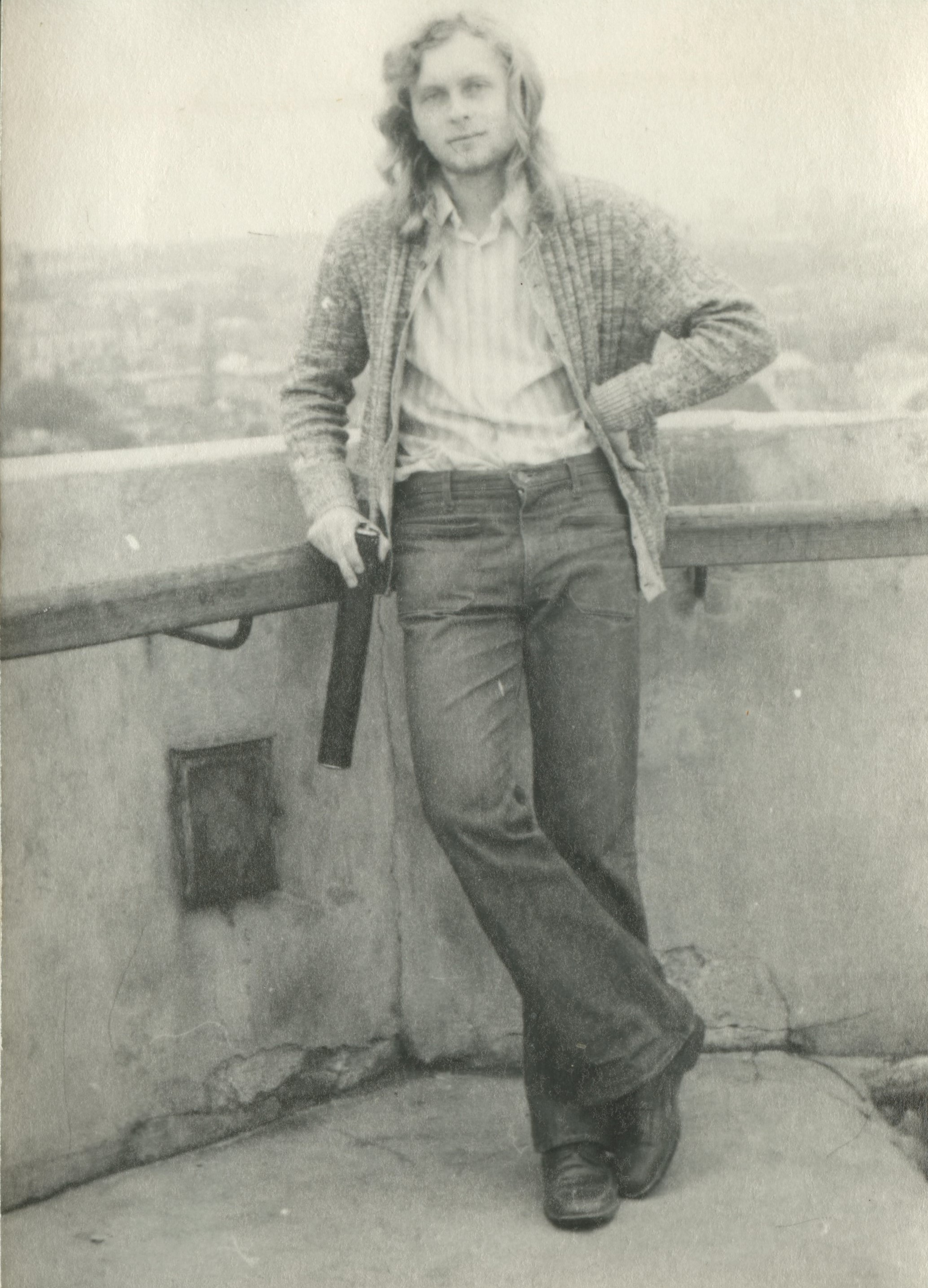

Jiří Kašpar was born on 23 August 1953 in Rychnov nad Kněžnou. He spent his childhood and youth in Kostelec nad Orlicí, a town famous for its underground scene and anti-regime activities. In addition to his studies, he was a musician and a sportsman. He dreamt of becoming a sports journalist, but in the end he obeyed his father’s wishes and went to study law. During his studies, he visited Lithuania, one of the countries of the then Soviet Union, as part of his summer activities. This trip confirmed his belief that not everything in the Soviet Union was as presented by the media of the time. After graduating from law school, he started working as an attorney in Polička. He and his wife founded and ran a film club in the town for several years. At the beginning of the 1980s, he met the Charter 77 petitioners, Mrs and Mr Homoala from nearby Pomezí. Their friendship did not escape the attention of the State Security and the subsequent reprimands from their superiors. Attorney Jiří Kašpar got off with only a mild exemplary punishment. After the crackdown on Národní Třída (National Avenue) on 17 November 1989, he became involved in the process of political change, was a founding member of the local Civic Forum and a city councilor after the first elections. He later joined the newly formed Civic Democratic Alliance (ODA). He continued to actively follow political events after his retirement. He retired from the practice of law in 2019 due to health reasons. In 2020, Jiří Kašpar lived in Polička.