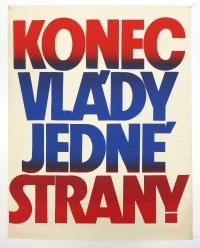

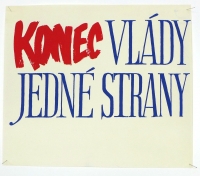

We printed for fourteen days straight

Download image

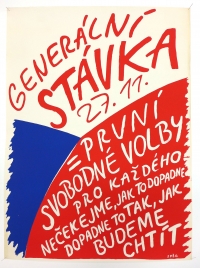

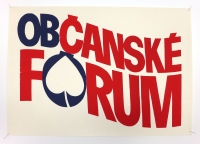

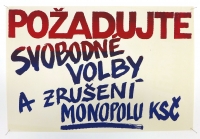

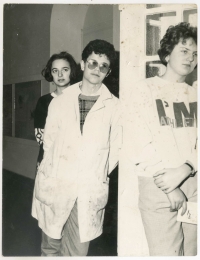

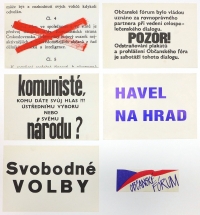

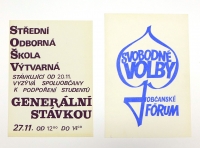

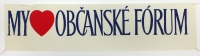

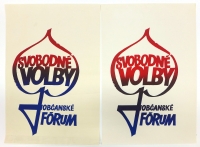

Petr Jurníček was born on 2 July 1971 in Prague. His parents soon divorced and his mother eventually found a new partner. Petr grew up in Bělá pod Bezdězem, Řevnice, and then mainly in Popovice u Berouna. Petr’s stepfather supported him in his interests and talents as well as his decision to apply to the then Secondary Vocational School of Fine Arts known as Hollarka, where he was accepted in 1985. In 1989 he graduated and immediately that same year began teaching screen printing at the school. In January 1989 he took part in the anti-regime demonstrations in the center of Prague during what was known as Palach’s Week; and when the Velvet Revolution began, Hollarka, thanks to students as well as a number of teachers, became one of the main centers of printing and the distribution of agitprop posters and flyers calling for support for the general strike and the Civic Forum. Today we can see these posters which flooded Prague and the entire country in the background of period photography and video footage from the days of the revolution. Petr Jurníček still teaches at the same school, which since 1990 has been under the name the Václav Hollar College and Secondary School of Fine Art.