Six weeks after giving birth, we were already working in the fields

Download image

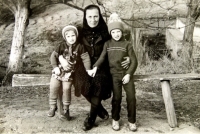

Amálie Jakubovská (Romanian: Iacubovschi), née Veverková, was born on 29 June 1940 and grew up in the Czech village of Šumice in the Romanian Banat. As a young child, she lived through the end of the war, when she and her family took refuge in the village. Her parents owned a small farm and from childhood involved her in agricultural work. After the war, her father’s siblings were included on the lists of re-migration transports to Czechoslovakia. However, the Amálie´s family refused to leave Šumice and continued to live there. She completed four grades in her hometown and after completing them she worked on the farm. She used to go to the market in Orsava, several dozen kilometres away. At the age of 18 she married a local musician, Jan Jakubovský, and together they raised one son. At the time of the building of Romanian socialism, they paid compulsory agricultural supplies to the state. Practically all her life Amálie worked on the farm. After the overthrow of the communists and the establishment of a pluralist system in the country, she was granted a pension from her late husband, who died in the late 1980s. With the opening of the state borders, she provided accommodation for tourists, which she ran until recently in Šumica. At the time of filming (September 2023) she was living there.