Mirek wanted us, the main members of the community, to take something like perpetual vows

Download image

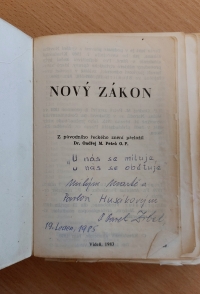

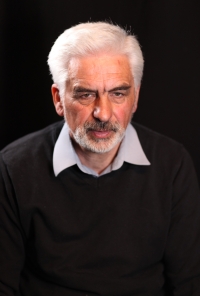

Pavel Husák was born on July 31, 1960 into a South Moravian farming family. He was brought up in the Christian faith, which belonged to the family tradition. During his adolescence he began to drift away from religion; under the influence of his materialistic upbringing at school he wanted to become an atheist and a “progressive”. In the 1970s, however, he met an older law student, Miroslav Richter, and this meeting made a deep impression on him. Miroslav Richter brought him to the Moravan congregation, and some of its members eventually formed the Society of St. Gorazd and Comrades. This community is nowadays classified as a Christian dissent - it maintained contacts with the underground church and carried out anti-regime activities. At the same time, as the Moravian Cherubic Choir, it performed with a liturgical band at official music festivals. Pavel Husák was one of the founding members and was especially active as technical support until his departure in the late 1980s. Even his family was unaware of his affiliation with the Society of St. Gorazd - Miroslav Richter was the witness’s brother-in-law, and so they passed off their meetings as mere family friendship. After the Velvet Revolution, however, their paths diverged, and Pavel Husák had no interest in entering politics with the original Gorazd family. In 2024, he was living in Těšany near Brno, still working in engineering and helping with repairs to a nearby hospice.