He grabbed a whip from the wall, swung it and shouted: Get out!

Download image

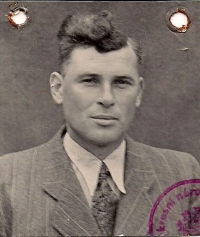

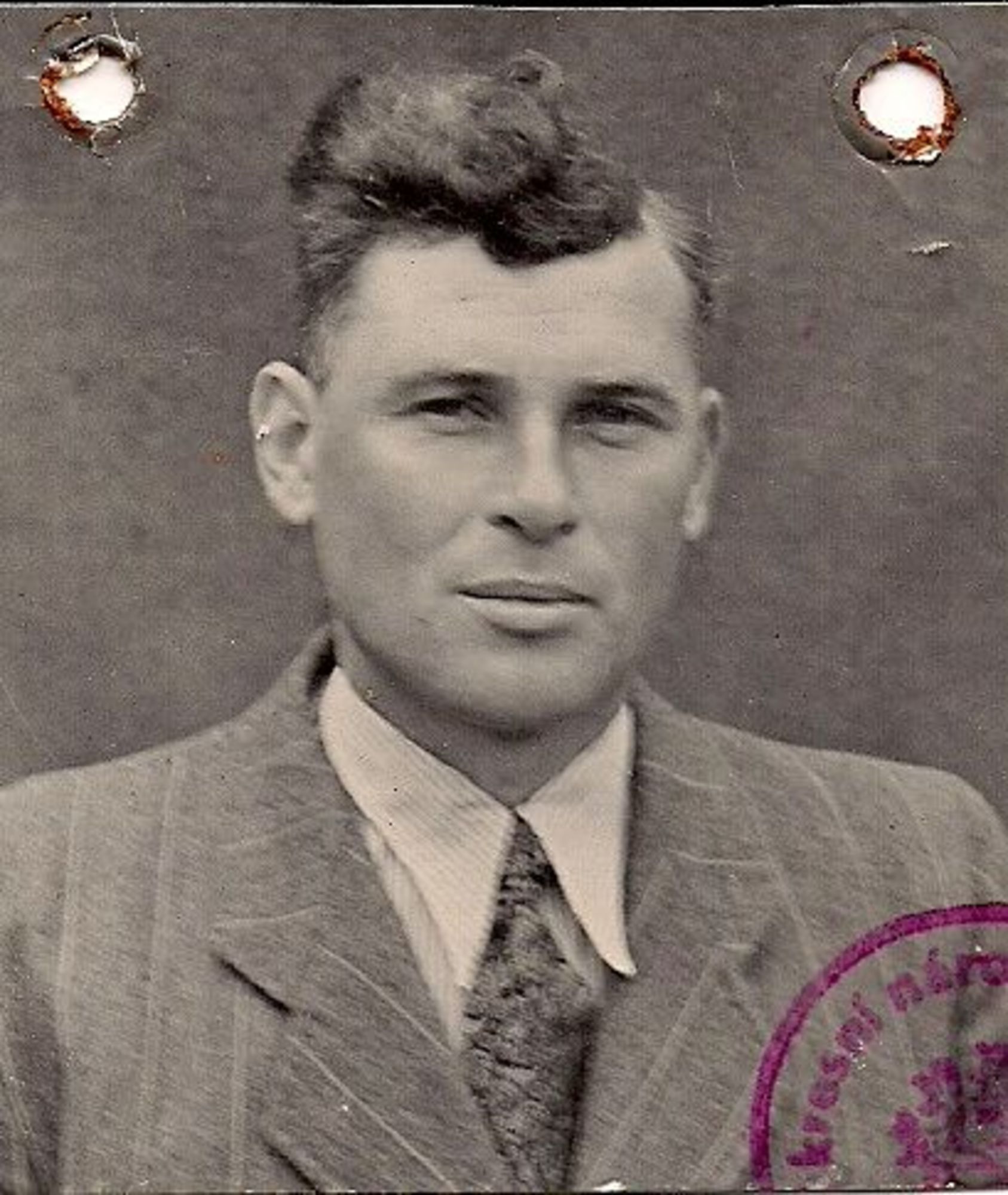

Ing. Zdeněk Horák was born in 1944 in Vyšovice in the Prostějov region. Most of the villagers were earning their living by farming before, but their life was forcibly interrupted by the collectivization of the countryside which was imposed by the communist regime. The Horák family owned the second largest farm in the village, and when they refused to join the cooperative during this process, his father, who was convalescing after a difficult surgery, was ordered to participate in an extraordinary military drill. He died as a consequence of the army exercise shortly after his return. When he was away for this army training, his wife was taking care of two little children and failed to deliver the prescribed quota of agricultural products for the state. In January 1953 she was sentenced for endangering the state economic plan to a penalty of 20,000 Crowns and to two months of imprisonment if she did not pay. The family was then forced to move out of their farm to a damp flat on the other side of the village. They had a difficult time making ends meet. After their father’s death, Zdeněk’s mother was not getting enough food stamps and in the currency reform in 1953 she lost the remaining money which she had been saving. The frequent checks on the family by the State Police also contributed to the family’s distress. The Horák family was allowed to return to their house only in 1960. Zdeněk had to work in the local agricultural cooperative since he was fourteen years old, and the cooperative’s leaders kept preventing him from continuing with his studies. Thanks to his ability and persistence, he eventually managed not only to complete a long-distance study of secondary school, but also to earn a degree from an agricultural college in 1987. After the fall of the communist regime, he purchased tens of hectares in the privatization process and today he is one of the most successful farmers in the region.