We were the first ones to go on strike in Pilsen

Download image

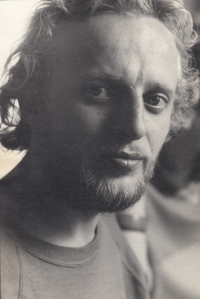

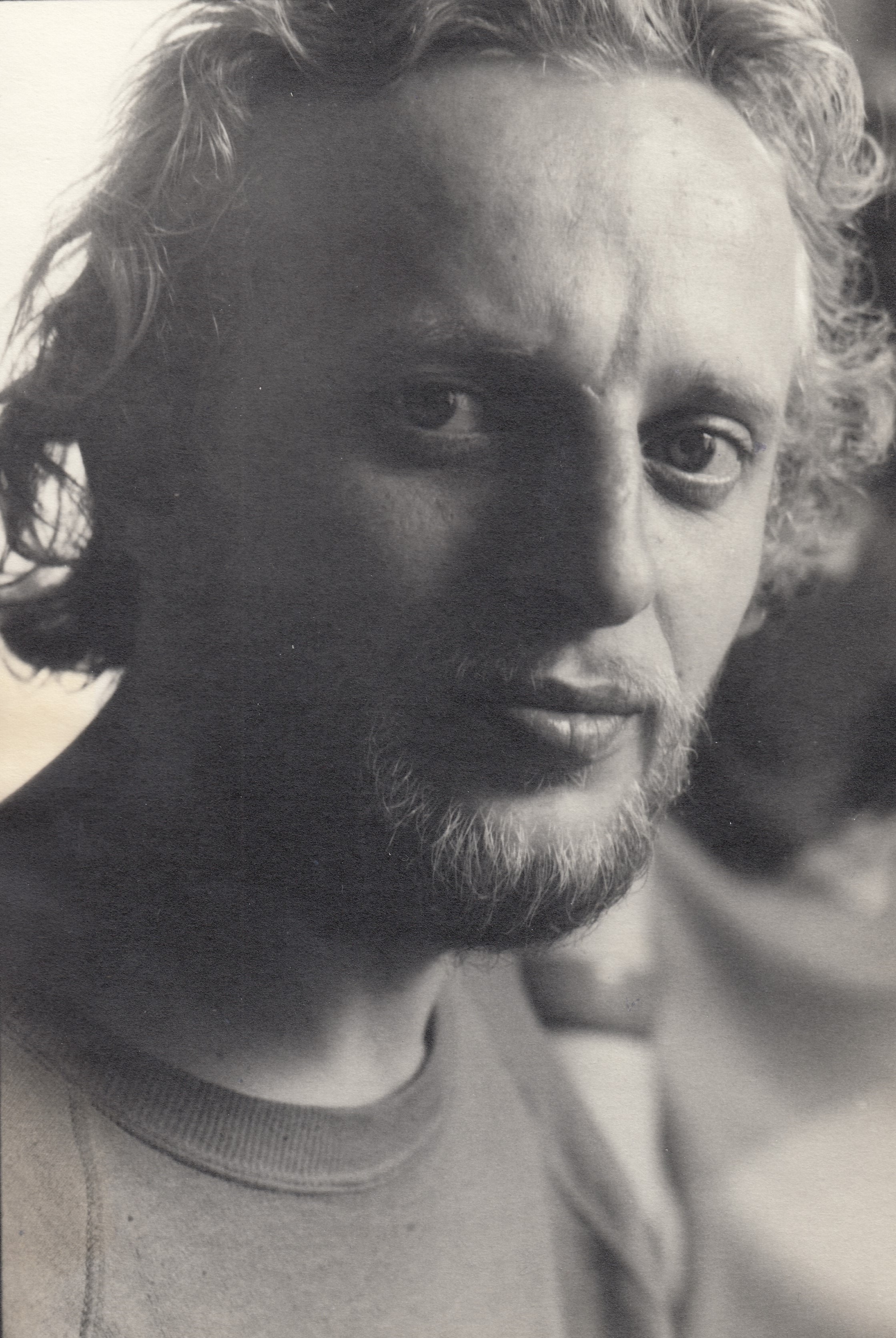

Bohuslav Holý was born on February 3, 1954. His father Bohuslav Holý was an Evangelical pastor. Under pressure from the State Security, he gave up his calling and worked as a labourer. His mother Anna Holá was a housewife. The Holýs had six children, which was not common in those days. At home, the family openly criticised the communist regime and exercised a great love of the arts and theatre. After the invasion of August 1968, during which Bohuslav was at a Boy Scout summer camp in Sušice, as a fourteen-year-old boy he started distributing newspapers bringing information about the occupation. Soon after, he started mingling with the revolting youth of Pilsen. Although he originally trained as a chemist, in 1977 he got a job as a stage technician at the Alfa theatre in Pilsen and in 1984, he joined the ensemble as an actor. It was in this theatre that he witnessed the events of the Velvet Revolution. During November 1989, he helped organise the strike of Pilsen theatres. In 1992, he married Klára Tomczová and together they had two children. After the revolution, he visited many countries with the theatre and was still working there at the time of the recording in 2022.