When I saw that I couldn’t make ends meet no matter what, I told myself that all I had left was a noose

Download image

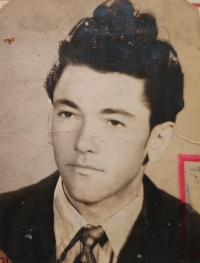

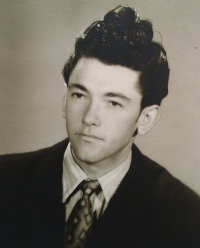

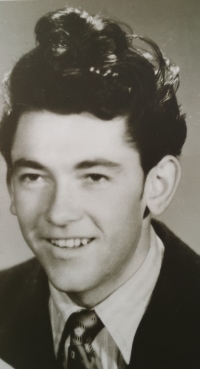

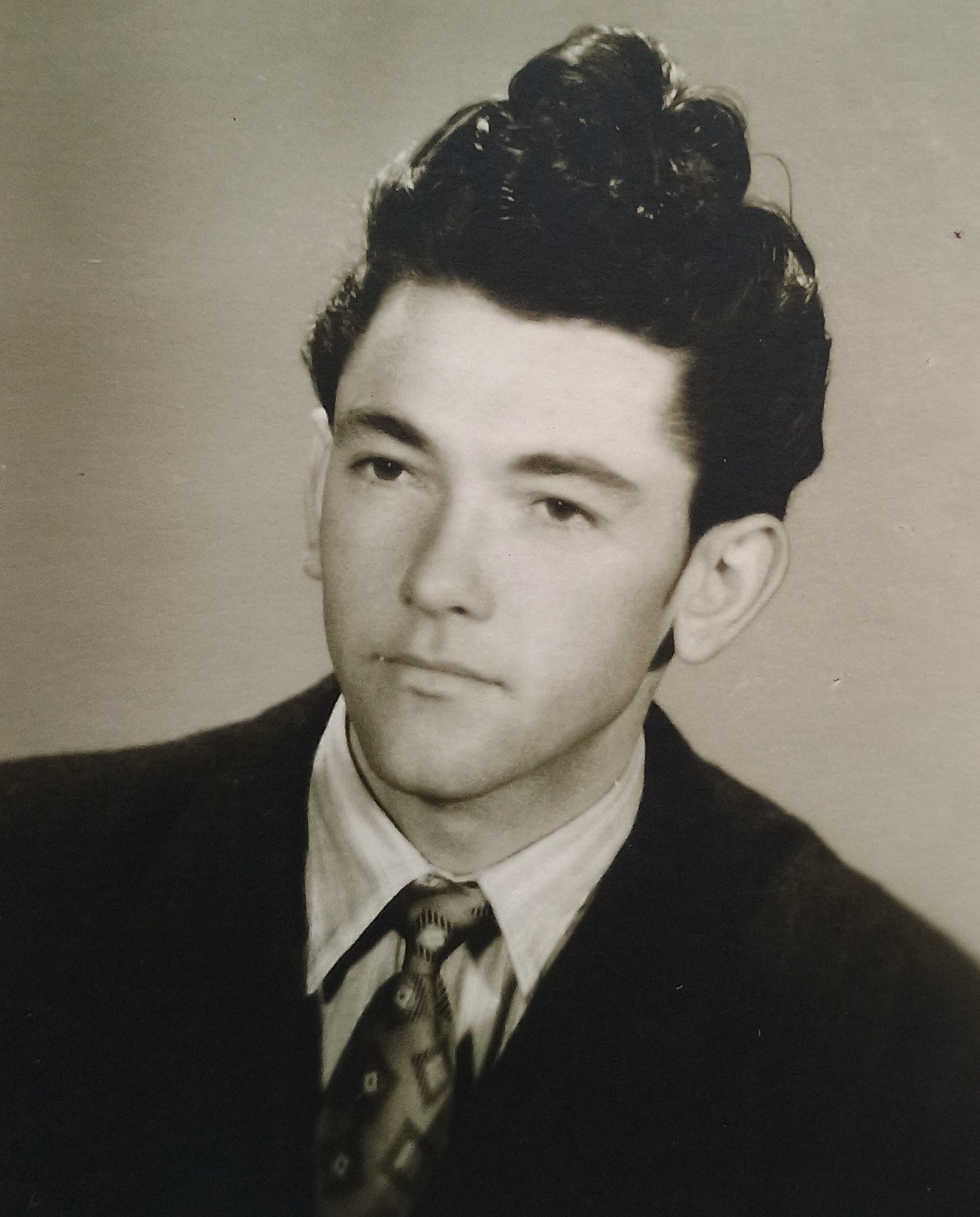

Josef Heldes was born on June 21, 1929, in Beckov, Slovakia. He spent his early childhood at his grandfather’s house because his father worked in France. After his father’s return, his parents bought half of a house below Beckov Castle. Josef witnessed the establishment of the Slovak state and the expulsion of the local Czechs. During World War II, he witnessed the transport of Jews from Beckov to concentration camps and the sale of their property. In April 1945, he experienced the bombing of Beckov, in which three residents of the village were killed. He also witnessed the violent behavior of Soviet soldiers during the liberation. After the war, the family moved to the border town of Kopřivná in the Šumperk region, where they farmed privately. After the communist coup in 1948, they faced pressure to join the unified agricultural cooperative (JZD). Josef Heldes’ parents joined the JZD in Kopřivná in 1950, but left again due to low financial returns. The family was then unable to meet their mandatory deliveries and faced imprisonment. There was no money to run the farm, so Josef took on various side jobs. He also worked in the Budoucnost cooperative, demolishing a mill left behind by displaced Germans in the former hamlet of Lesní mlýn, which no longer exists. In the end, he decided to return to Slovakia, where he worked as a tractor driver on a state farm. Around that time, his parents rejoined the JZD, and a few months later, they fled Kopřivná and joined Josef in Slovakia. In 1959, Josef returned to Moravia. He lived in Staré Město and nearby Stříbrnice and worked as a laborer in state forests for over 40 years.