In August 1969, playing the hero was no longer an option

Download image

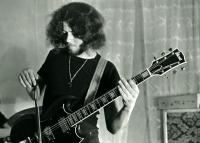

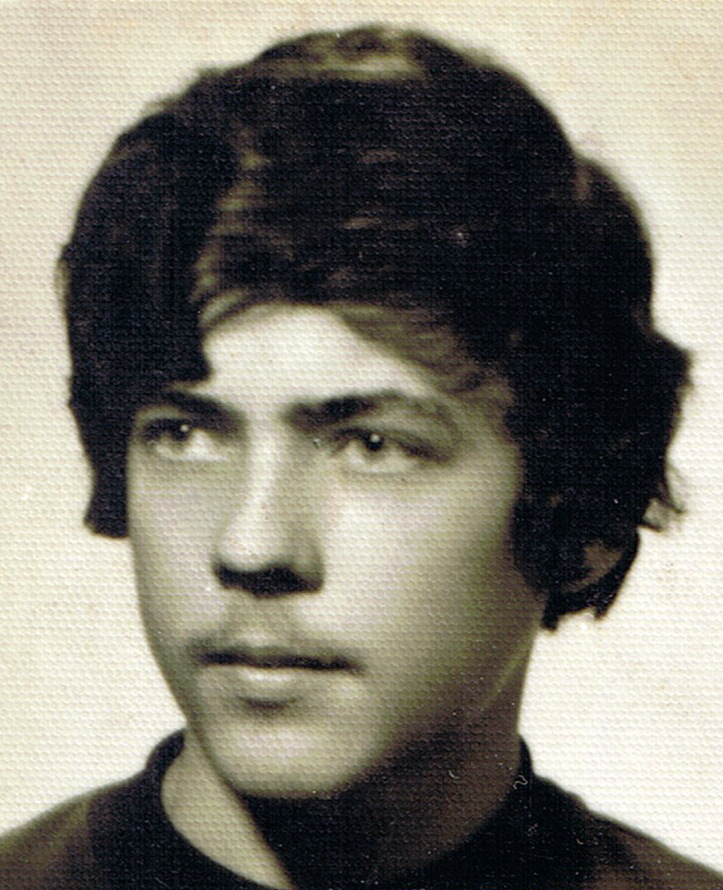

Petr Hejna was born on 12 January 1955 in Prague. He came from a clerk family, his father was a member of the Communist Party. His father was expelled from the party in 1970 and took it very hard. His great personal disappointment was one of the causes of his subsequent complicated relationship with his son. In 1966, under the guidance of Jiří Zachariáš, Petr joined a Boy Scout group. He was 13 years old when Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Warsaw Pact troops and Petr, depending on his ability, actively joined the resistance against the occupiers. He was distributing leaflets and began to compose protest songs. A year later, he took part in mass demonstrations in the centre of Prague, which were brutally suppressed by the authorities. He graduated from the Secondary Technical School of Graphics, which brought him into contact not only with the bohemian milieu, but also with some of the personalities from the dissent. After finishing his military service, he began working as a children’s homes carer. He criticized the conditions there for a long time and shortly before the Velvet Revolution, feeling disappointed and powerless to change anything, he quit his job. After 1989, he set his own business, first in the jazz club Agharta, and later he founded his own music club. In 2021 he was living with his second wife on a farm in Třebkov, a small village near Písek.