First and foremost you should deal with the evils done in your nation’s name

Download image

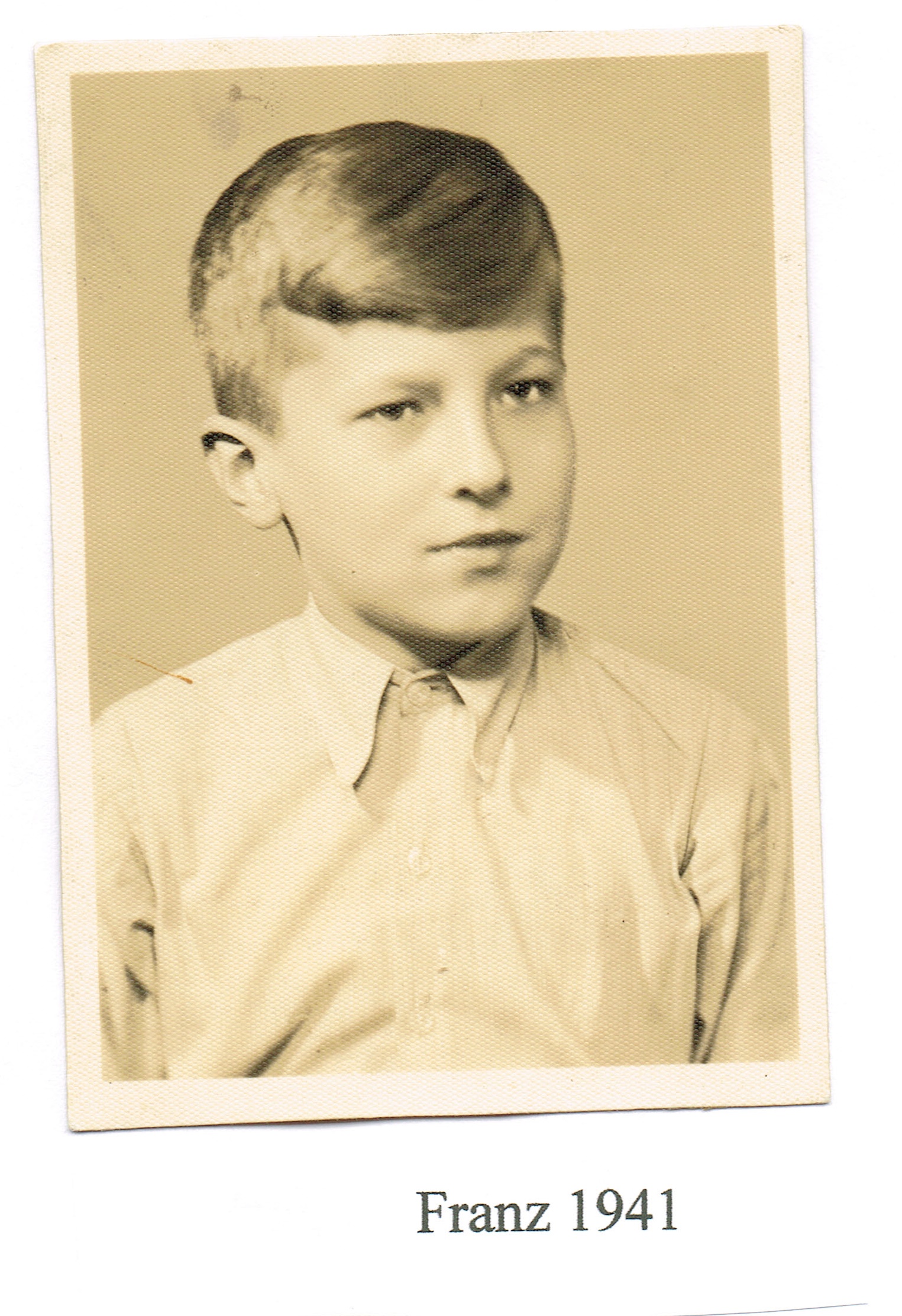

Franz Gruss was born on 1 January 1931 to a German family with partially Polish and Czech roots in the Moravian town of Ostrava. His mother spoke Czech, but the family talked exclusively in German. He only talked Czech with his grandmother and “on the streets”. His father was a printer, his mother ran a tailor’s shop in their spacious flat. After the German occupation of Czechoslovakia (Mr Gruss uses this term himself), the entire family were given German citizenship under the Reich. Franz entered the Deutsches Jungvolk (ages 10-14 in the Hitler Youth), his older brother was conscripted and died in 1943 in Crimea and because of his age their father was not forced to join the war. Franz has a dim recollection of his half-Jewish classmate and being told about the Ostrava synagogue fire. After the first bombing runs hit Ostrava, he left for the boarding house in Frýdek-Místek, where among other things he was subjected to military indoctrination and to this day remembers the antisemitic children’s songs. He spent the end of the war with his aunt in the town of Lom near Most. There in the Duchcov area he witnessed the lynching of a Canadian pilot, in May also the arrival of the Soviet Army, the murder of his German neighbour by Czechs as well as the procession of the local German population (including his uncle Josef) to the church, where they were murdered. On the train back home from Lom to Ostrava he and his parents were arrested in Přerov, his father imprisoned and tortured. After Franz and his mother were rejected by their Czech uncle and subject to aggressive treatment by the Revolutionary Guards (and being saved by a distant Jewish acquaintance), they were interned in the “Mexiko” camp and sent out to work the fields. He and his parents were soon declared unfit for work and marched to Opava and the next day to the borders. On the way he witnessed people falling exhausted into ditches. They were collected in a forest clearing and sent through a section of woods with landmines over the border, which was already Poland at the time. There he lived a year and a half, working for the local German farmers and interpreting for the Polish soldiers, until the final phase of the expulsion of Polish Germans, which the entire family joined. They were then deported to the GDR and Franz studied at a business school in Leipzig, until immigrating to West Germany in 1951 (at night, illegally in a cargo train). Today Franz lives near Heidelberg, after retirement he does travel guide work, especially in Poland, but also the Czech Republic. He is learning Polish and Czech. “First and foremost you should deal with the evils done in your nation’s name” he says. Among other places he also takes tourists to see Auschwitz.