He cooked for the communist leaders and later dug mines with dynamite

Download image

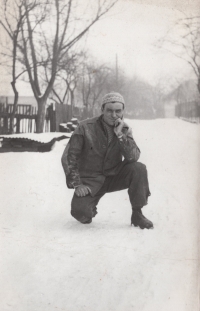

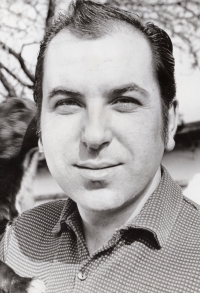

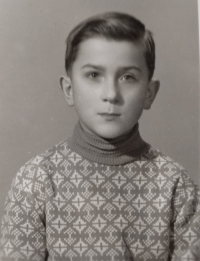

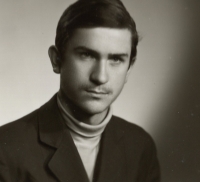

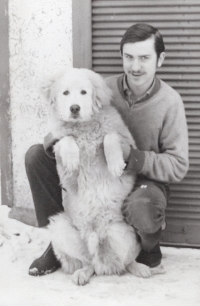

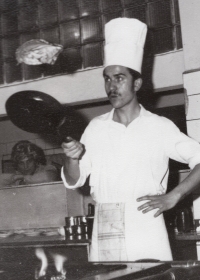

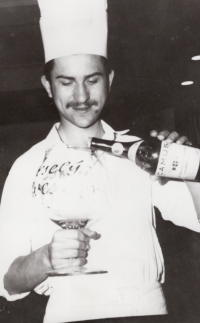

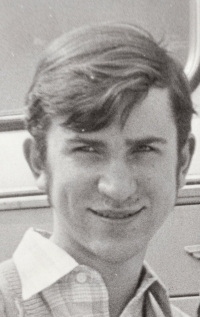

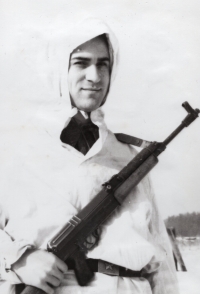

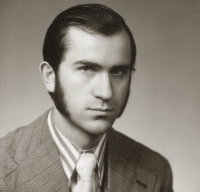

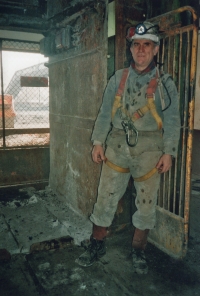

Josef Grobelný was born on 29 November 1953 in Dětmarovice. His father František worked as a joiner and his mother Marie was employed by the railway. He lived through the August 1968 occupation as a 15-year-old boy at the pioneer camp in Valašské Klobouky. His father confiscated his air gun for fear of the occupiers. Although he longed to work as a forester, he trained as a cook in Český Těšín and joined the Hotel Jelen in Karviná. Thanks to his skills, he prepared meals even for high communist officials. From 1972 to 1974 he completed basic military service with the Border Guard at the Dolní Dvořiště and Cetviny companies, where he worked as a cook and a member of the patrol. For financial reasons, he later left the catering industry and joined the Ostrava-Karviná Mines Construction Company. He passed the examinations for a gunner and participated in the digging and excavation of the mines ČSM, Darkov, 9. květen, ČSA and Doubrava. During the demanding work underground, he survived a fall into a mining pit and a cave-in with loose rock. After 1989, he participated in the liquidation of the mines and personally supervised the backfilling of the pit at the Dukla mine. He retired in 2011. In 2025, Josef Grobelný lived in Dolní Lutyně and guided visitors around the former Michal Mine in Ostrava.