On the first date he told me he would marry me

Download image

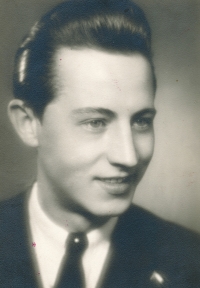

Biography Zofia Faiglová, née Jankovjac, was born on March 30, 1923 in Poland, in the Poznań region, in the town of Plešev (Pleszew). She was the eighth child of the Jankovjacs who had a farm and ran a cart business. Zofia experienced the outbreak of war in Gdynia on 1 September, 1939, near the epicenter of the first battles of World War II. She was supposed to attend secondary business school, but in Poland the schools closed and she could never complete her education. In 1942 she was totally deployed to Germany in the town of Altenburg in the arms factory Hugo and Alfred Schneider. In August 1944 she met her future husband, Antonín Faigl, a totally deployed Czech student. In March 1945 he and his Czech friends fled to the Protectorate. They could not take the witness because, as a Polish national, she would risk much more than the Czechs. After the liberation in May 1945, Zofia worked for half a year in Germany in the UNRRA (United Nations Administration for Assistance and Reconstruction) and in November 1945 set out to transport to Kladno to see Antonín. They married in the spring of 1946. Zofia acquired Czechoslovak citizenship, but never had enough time to complete her education. In 1948 she gave birth to a baby girl who died of pneumonia after 14 days; then three sons were born. The Faigl lived in Kladno, Chomutov and Prague. Throughout her life, the witness worked in the hospitality industry as a waitress and restaurant manager. She was not interested in politics.