One girl spat in the face of a Soviet soldier. He didn’t even say a word and cried

Download image

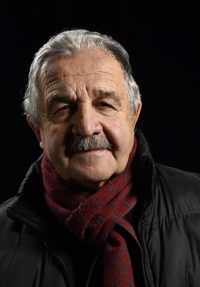

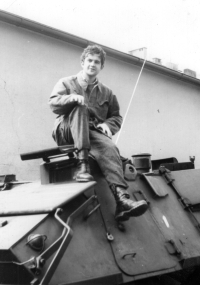

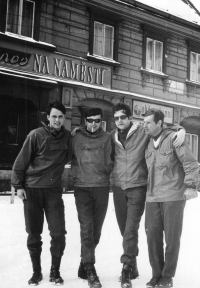

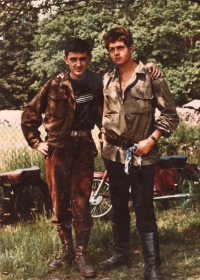

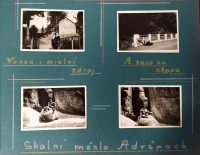

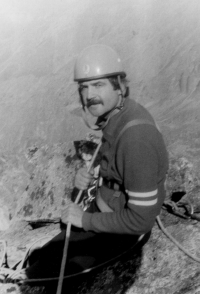

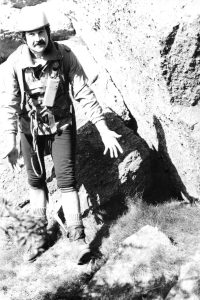

He was born on August 4, 1948 in Liberec, where his parents immigrated in 1945 and bought a family house in Ruprechtice district. Here he grew up with his brother František, who was three years older, his parents and grandparents from his mother’s side. His father worked at LIAZ (Liberecké automobile factories) as a locksmith, his mother was a milliner. After elementary school, the witness trained to be a metal grinder and machine tool mechanic at LIAZ. From a young age, he did a lot of sports - he went cross-country skiing, skiing on Ještěd, and from the age of thirteen he engaged in competitive fencing. From the age of fifteen, he also went out on hikes, twice instead of hiking trips, the members of State Security Service took him from the railway station in Turnov to JZD (Unified Agricultural Cooperative) Doksany for the singling of beets. In 1967, he enlisted for basic military service, spent it in the Na Míčánky barracks in Prague-Vršovice, where units guarding objects of special importance were based. On August 21, 1968, he experienced the invasion of the troops of the five countries of the Warsaw Pact in Liberec, where he was on vacation at the time. In the center, he witnessed the shooting of Soviet soldiers and the crash of a tank into the archway in the main square. After returning from the military service, he joined the famous Liberec Research Institute of Textile Machinery (VÚTS), which after four and a half years he exchanged for work in the mountains - first as a ski lifter under TJ Ještěd and later as a professional member of the Jizerské Hory Mountain Rescue Service. During his twenty-eight years of service, he provided first aid to visitors to the mountains, built Mountain Rescue Service stations, lifts and slopes, and qualified as a mountain guide to lead mountain expeditions. After leaving the Mountain Rescue Service in 2006, he worked for five years as a dam keeper at the Černá Nisa dam. In 2022 he lived in Česká Kamenice.