I approach new things feeling confident that I can do it. And it usually turns out well

Download image

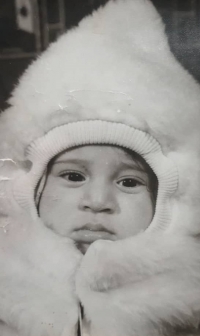

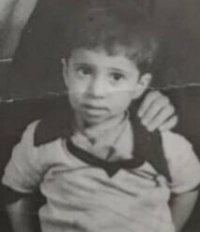

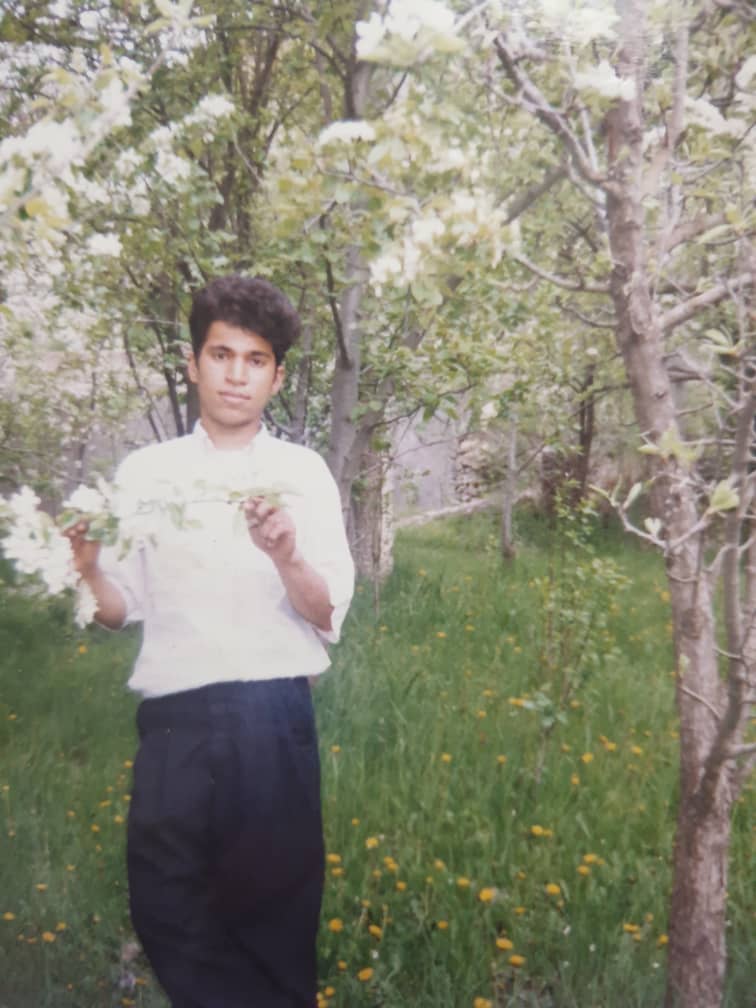

Javad Cihlář, whose birth name was Rezai, was born to Afghan parents on 20 April 1989 in Mashhad, Iran. His parents fled to Iran because of the dangerous situation in their country. It was supposed to be a short-term refuge that eventually extended to twenty years. He grew up with his mother only. His father never returned from one of regular trips to Herat, Afghanistan. The family believes he was murdered by Taliban members. The mother started to make living for herself and her son as a seamstress. From the age of six, he helped out in a tailor’s shop. He did not attend school because his documents were missing. Later, his mother became seriously ill and died in 2008. In this precarious life situation, as a friend urged him to do, he decided to go to Europe. He and a group of other refugees sailed from the Turkish coast to Greece by boat. From there, he took a truck across Italy to the Czech Republic. He found a new home in a country which he hadn´t had idea existed before. After a difficult start in refugee centres, he managed to find work in a renowned tailor’s shop in Prague. At the same time, thanks to his friendship with a Czech language teacher, he began to participate in the church life of the Unity of the Brethren Baptists. In 2012, while cooperating with the non-profit organization Multicultural Centre of Prague, he met his future wife. The same year he joined the educational project “Stereotypes in us” for Czech students at the Multicultural Centre of Prague. He moved to Brno, where he runs his own tailor´s shop. He is currently (2019) learning to drive and remarks with a smile that there is no better Czech language textbook than a traffic rules handbook for driving schools.