You get one in the gob, that can happen, that’s not so bad

Download image

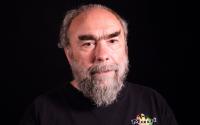

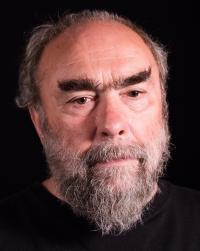

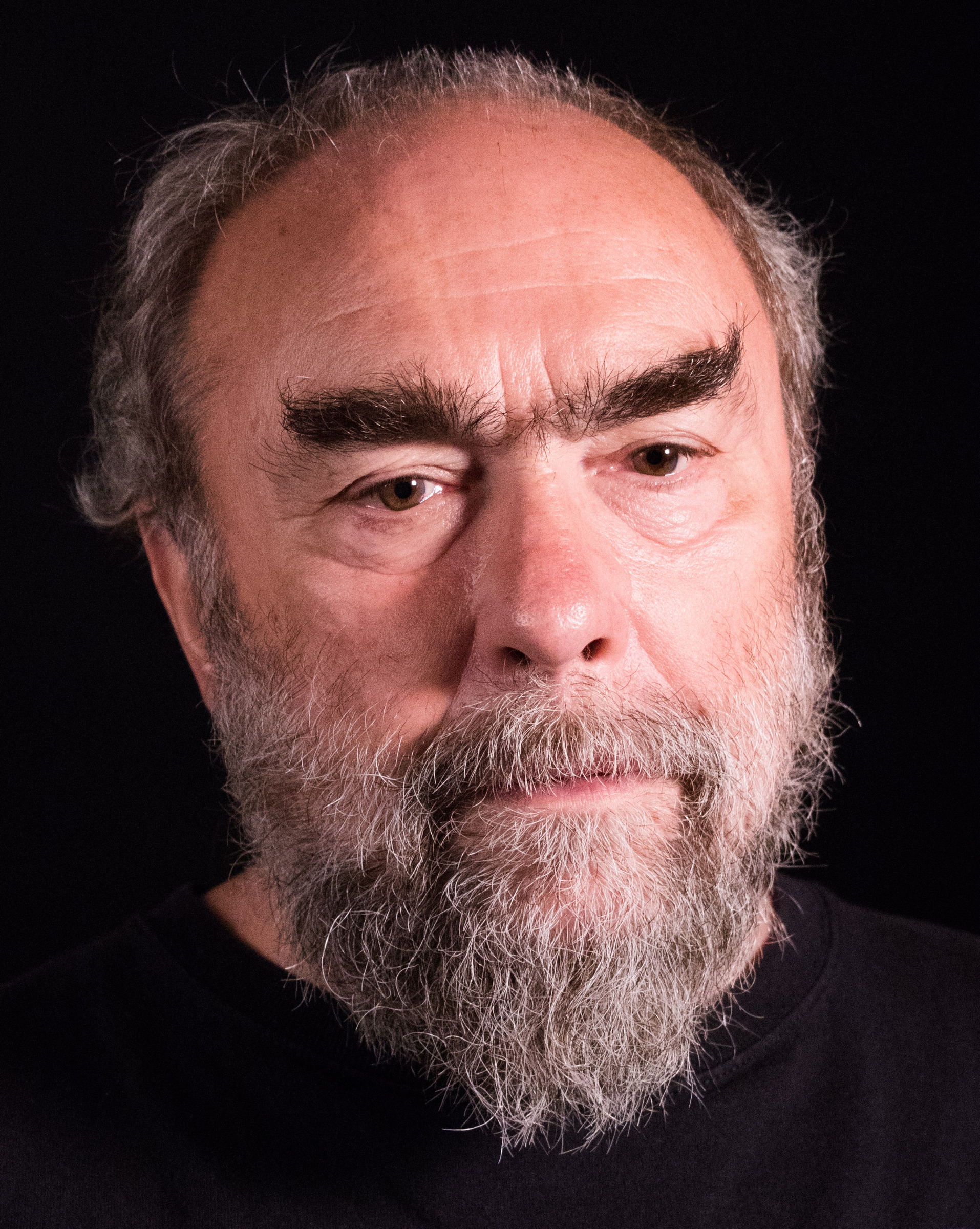

Aleš Březina was born on 12 July 1948 in Prague. After attending primary school in Vršovice and a secondary communications school, he was accepted to study at the Evangelical Theological Faculty of Charles University, from which he was expelled in 1972 for political reasons. He became active in the alternative “underground” culture and was one of the first people to sign Charter 77. After refusing summons to mandatory military service, he was arrested and sentenced to two and a half years of prison. He was interned in Libkovice and Pilsen-Bory. After his release he again refused to serve in the army and was threatened with another prison term, this time for four years. He decided to emigrate to Canada, where he worked with Josef Škvorecký; he was employed as a journalist at Nový domov (New Home), a sports commentator for the Toronto Star, or a commentator of hockey matches of the Canadian Cup. He is the author of the book Řetěz bláznů (Chain of Fools) and the co-author of the books Řecké pašije - Osud jedné opery: Korespondence Nikose Kazantzakise s Bohuslavem Martinů (The Greek Passion - The Fate of an Opera: The Correspondence between Nikos Kazantzakis and Bohuslav Martinů) and Kings of the Ice Hockey.