They aimed a gun at me. I covered myself with the blanket and thought they’d shoot me

Download image

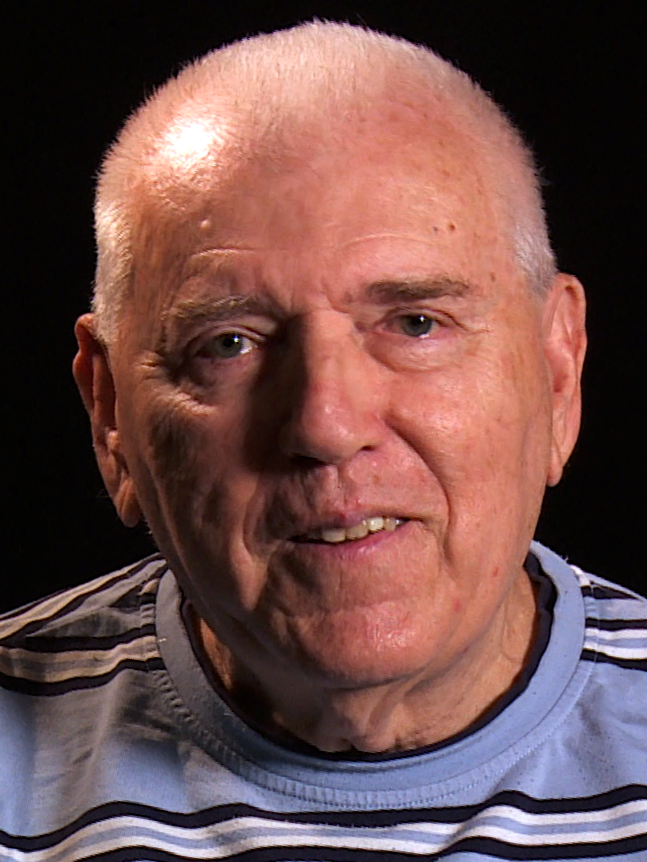

Štěpán Böhm was born on 29 November 1938 in Tasovice in the Znojmo region in a partially German family of Alžběta and Štěpán Böhms. Due to their German origins, the family was not expelled from Tasovice in the Sudetenland after the Munich crisis. The father was forced to join the Wehrmacht in 1943, was captured by the Russians and then the Americans, and did not return home until after the war. Štěpán remembers the bombing of the Znojmo area in 1945 and soviet liberators’ violence. As part of the post-war movements, the witness’s grandfather and his father’s siblings were compelled to leave Tasovice. Grandfather Jakub was shot by the revolutionary guardsmen on Štěpán’s watch during the deportation. The family moved to Karlovy Vary in 1947 where Štěpán completed his primary education and then graduated from an automotive technical school in Zábřeh na Moravě. He achieved success in 1962 in the Zelená Marsu (Green Light for Mars) competition focused on innovation; he was working at Závody průmyslové automatizace in Trutnov at the time. As a reward, he went to Cuba, but the Cuban Missile Crisis burst out and his three-week trip eventually took one year – he was unable to leave Cuba for safety concerns. Štěpán Böhm held several jobs, mostly in the Karlovy Vary area. He retired due to health problems in 1972. During the Velvet Revolution, he was active in the Civic Forum in Karlovy Vary. He moved to Brno in 2002 and was still living there when he was interviewed by Memory of Nation (2022).