The son of the Clay-Eva sortie commander grew up among traffickers. He came back home after twenty years

Download image

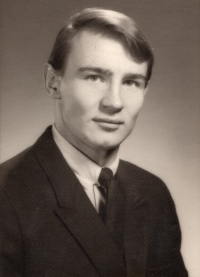

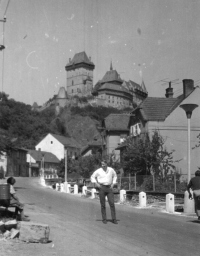

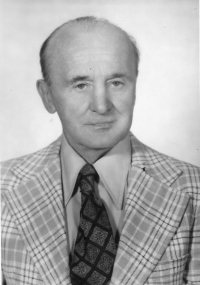

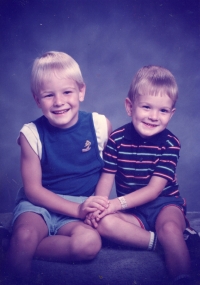

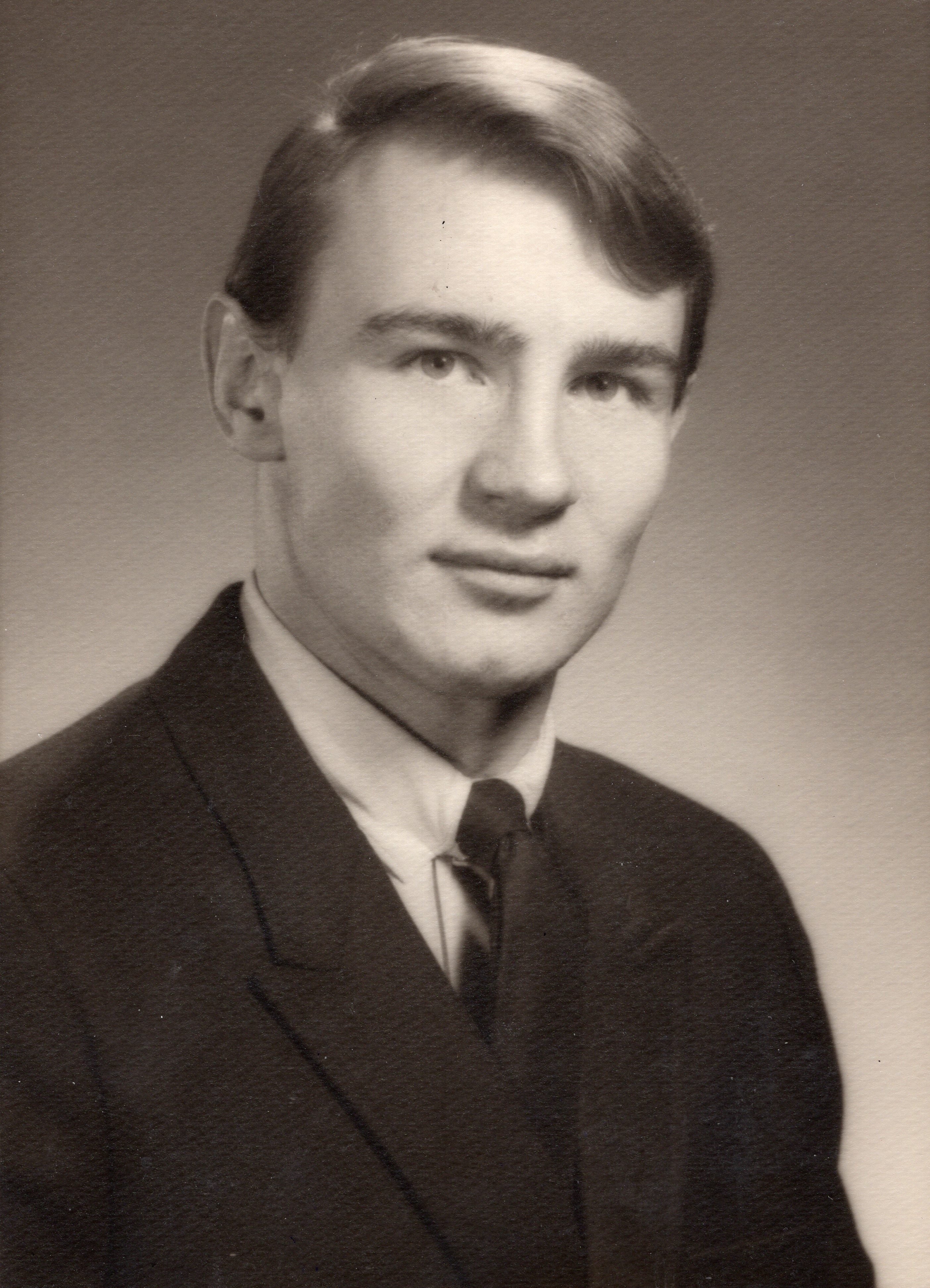

Antonín Bartoš Jr was born in Lanžhot on 26 July 1946 and his life was strongly shaped by his father’s destiny from an early age. Antonín Bartoš Sr fled to England during World War II and took training to become the commander of the Clay-Eva sortie. The group operated in the east of Moravia in 1944 and 1945 and its primary task was intelligence activity. After the war, the witness’s father was a MP for the National Socialist Party and spoke openly against the communists. They tried to imprison him after the February 1948 coup but he fled and left for France with his family. In Paris, the Bartoš family operated the Maryša restaurant for Czechoslovak émigrés, with communist spies monitoring them. In 1950, Antonín Bartoš Sr entered service again under General František Moravec. In Germany, he trained couriers and traffickers who would operate on the Czech border, and gathered intelligence. Two years later, the family decided to relocate to the USA where the witness’s parents held civilian jobs and engaged in social life with fellow émigrés. Antonín Bartoš Jr went to both American and Czech schools from an early age and graduated in electromagnetics. He visited Czechoslovakia for the first time after his emigration in 1969. The StB monitored him all the time but he would come back repeatedly. He married Radmila Lebedová in 1976 and the couple had two sons, Jan and František. As part of his career, the witness was involved in the development of various radar technologies for US Navy and intelligence services. His father died in 1998 without receiving his Czech citizenship back. The witness continued to visit the Czech Republic, keeping in touch with the families of the other people connected with Clay and taking part in memorial events regularly. He lived in the USA in 2022.