He who went straight was bent with a truncheon, he who went bent was straightened with a truncheon.

Download image

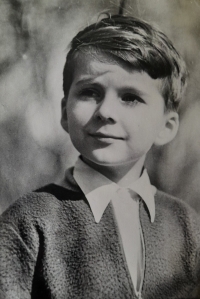

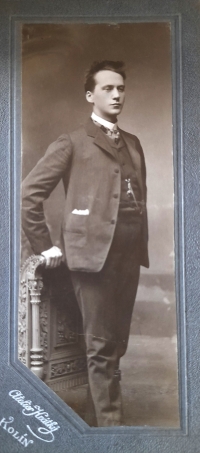

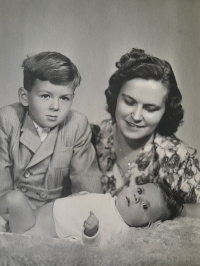

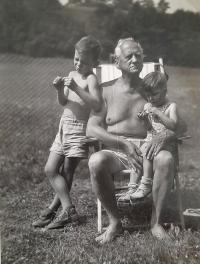

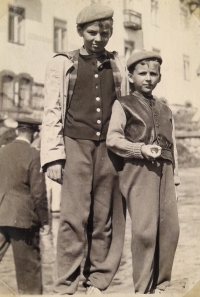

Jiří Hajner was born on 8 April 1949 in the Vinohrady Maternity Hospital in Prague. His father Josef was a typographer and typesetter, his mother Libuše took care of the household. The family was well situated, mother’s parents, the Cvejns, owned a house in Nusle. After the divorce of his parents, Jiří Hajner stayed with his four years older brother and his mother, who was negatively impacted by the divorce and could not cope with taking care of her two sons. Jiří therefore spent a lot of time in children’s homes. He trained as a turner in the Czech Industrial Works, where he worked for thirteen years. From the age of fifteen he earned his own living and at the age of twenty he married and started a family. In the sixties he spent most of his free time in groups of Prague boys, belonging to the so-called “CKD”. In August 1968, he witnessed the events surrounding the extraordinary congress of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, photographed the invasion of Warsaw Pact troops in the streets of Prague, and fled from the shooting of Soviet soldiers. He was a member of the Scientific and Technical Society and had over ten improvement proposals to his credit. In 1977, he was fired from ČKD because he questioned the company’s opposition to Charter 77, which management demanded of employees. Thereafter, they did not want to employ him in state-owned enterprises. He was eventually hired at the Motex manufacturing cooperative, which produced diagnostic measuring equipment for vehicles. At the end of the 1980s he participated in anti-regime demonstrations, and during Palach Week in January 1989 he was detained by the Public Security Service (VB) and brought for interrogation in Bartolomějská Street. In 2023 he was living in Prague.