During the war, they helped their neighbors, who then took everything from them

Download image

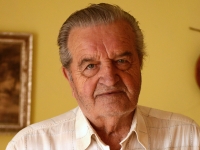

Josef Zíka was born on June 26, 1931. He grew up on his parents’ farm in the village Rozsedly near Sušice in Pošumaví near the Czech-German language border. From an early age, he was meeting German neighbors with whom his family had very good relations. He perceived Czech-German friendships even more intensely when the family farm became a shelter for forced German Wehrmacht soldiers. Soon after World War II, the family came into conflict with local members of the Communist Party. The conflict even deepened after the rise of the Communist Party in 1948. The Zíka family faced various forms of pressure to transfer their large farm to the newly established united agricultural cooperative (the state collective farm). At that time, Josef Zíka was sent into the military service to a working group of detached battalions and later Auxiliary Technical Battalions. During his service, he had to travel around the country without facilities and perform very physically demanding work. After the witness’s return from the military service, the farm was already part of the local collective farm. Josef Zíka moved to Eastern Bohemia. During the period of normalization, he contributed to the establishment of a gardening settlement near Týniště nad Orlicí, which is named Zíkov after him. The Zíka family acquired the native farm in Pošumaví in the restitution. It was in a devastated condition. The farm is being restored by the witness’s grandson nowadays.