“We’re under attack, we need help!” we broadcast from the airport on August 21

Download image

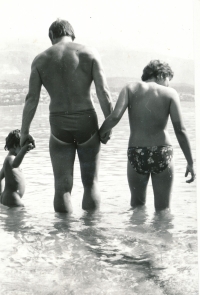

Miloš Zídek was born on 3 December 1940 in Prague. His grandfather Josef Doležal, the mayor of Sokol in Vinohrady and one of the founders of Legiobanka, was arrested in 1949 and died after five years in detention from the consequences of communist imprisonment. For a long time it looked like Miloš would be just a metallurgist, but eventually his family managed to get him into the engineering field with a high school diploma. After the war, where he learned to use radar technology, he became an air traffic controller at Prague-Ruzyně airport. He was involved during the Prague Spring and during the August 1968 invasion he secretly sent out cries for help from the airport. This later brought him long-term trouble with the State Security, which blackmailed him and tried to recruit him as a collaborator. In 1974 Miloš Zídek became head of the regional air traffic control centre, although he was not a member of the Communist Party. During his tenure there were several hijackings of aircraft to West Germany. In 1984, he and his daughters went to North Yemen to join his wife, an expert in radiology, who had obtained a job at a hospital in Sana’a. Both spouses were under State Security surveillance in Yemen. Helena Zídková left prematurely after a few months. Miloš Zídek made a dramatic escape to Czechoslovakia, where he resumed his career as an air traffic controller. After the Velvet Revolution, he worked as an expert in air navigation and later moved to the private sector, where he continued to work on the modernization of navigation systems. In 2024, he was living with his wife in Nižbor.