I was not a model soldier. I did not want to fight with others, I did not want to lie and deceive

Download image

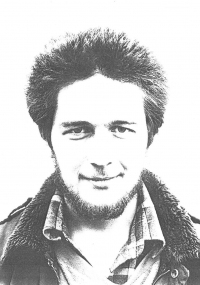

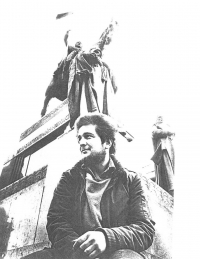

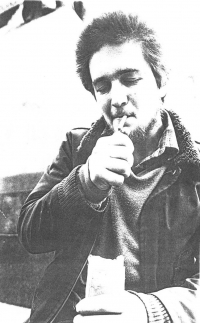

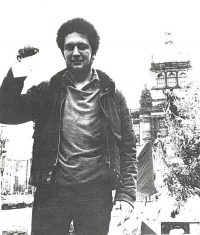

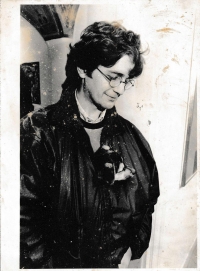

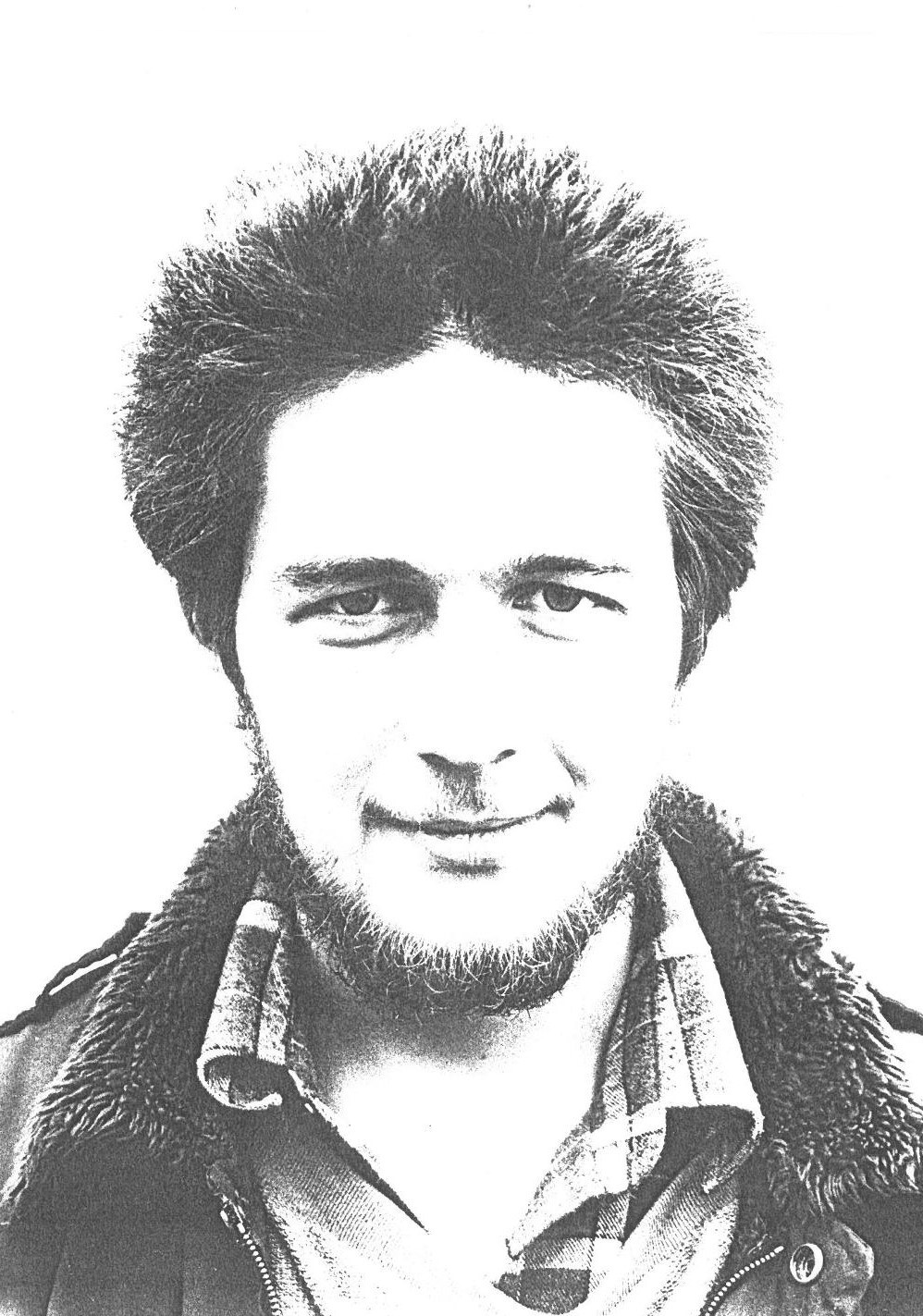

Alexej Ženatý was born on 6th March 1971 in Rynki in Kurgan Oblast under the name Alexej Kuzevanov. He studied electrical engineering. In March 1989 he had to start his compulsory military service and he was sent to then Czechoslovakia. He was not able to deal with the ubiquitous humiliation of soldiers nor with the propaganda and political education which he soon understood as untruthful. Already in autumn 1989, after half a year of service, he left his garrison without a permission. However, he was captured and punished by imprisonment in fortress Josefov near Jaroměř. Due to the lack of mechanics, the Soviet military command returned him in a short time to service in garrison in Boží Dar near Milovice and later in Mimoň. The disputes between him and his officers continued and in the beginning of November 1990 he deserted. On 8th November with the help of Czechoslovak police officers he got into the centre for refugees in Krásná Lípa where he applied for political asylum. The documentarist and director Vladislav Kvasnička (1956–2012) found him there and offered him help. He gave publicity the story of Alexej Ženatý, arranged the attention of politicians and found for him a convenient shelter with the family of evangelical pastor (currently the Synodal Senior – the highest representative of the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren) Daniel Ženatý. Alexej spent almost two months with the Ženatý family, since 19th November to 8th January 1991. At the end of December 1990, he obtained the official status of a refugee. He is the only one of the Soviet deserters who stayed in Czechoslovakia. In 1997 he acquired a Czech citizenship and changed his surname to Ženatý. During the recording the witness still lived in the Czech Republic, in a small village at the borders of Bohemia and Moravia.