“I don’t understand how we were, what a force it was, that we met, just us, just like we are, even without acting schools.”

Download image

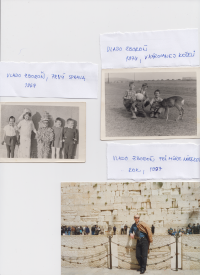

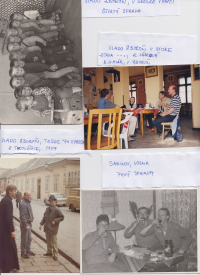

Vladimír Zboroň was born on November 5, 1960 in Námestovo, into a working-class family with peasant roots. He lived with his parents and five siblings throughout his childhood in the village Oravská Polhora. Father Vladimír worked as a driver and mother Jolana was a cook. Very often, Vladimír’s parents did not have it easy, so they mostly carried mainly about place for sleeping and about food. The memorial did not leave his homeland for almost his entire childhood and did not get into the city until he entered high school. As a child, he enjoyed visiting log cabins, local lakes and loved football. However, he did not have much time, because as the eldest son, he had to help around the yard, graze cows, bring out manure or clean the barns. These memories were not the most beautiful, later he was reluctant to work around the house. Vladimír chose as a high school, a grammar school in Námestovo. It meant leaving of the home village and discovering new possibilities. He became a spark-child, a pioneer and a bundle-man. For the first time, he began to perceive political events. In high school, he learned about hatred of Russians or the regime at that time. After completing two years of compulsory military service in Sabinov, he decided to return home because he did not know what to do with his life. Under the influence of conversations with local chaplains, in 1984 he went to study at the Faculty of Theology in Bratislava. He participated in secret meetings of dissent, in the company of educated people, such as Sklenka, Lec or Demeš. In 1987, due to inappropriate behavior, he was expelled from school. Due to fear, he could not return home, so he remained to live in Bratislava. After a demanding search because of his past, he managed to get a job in Zares. He worked as a storekeeper. During the revolutionary years, he lived quietly. In 1988 he decided to attend an evening school of acting in the House of Culture, in Dúbravka. After the revolution, in May 1991, he received an offer from Jožo Chmela to become a part of the Stoka Theater, which was founded by Blaho Uhlár and Miloš Karásek in the same year. His first performance was Impas, in which Vlado took part for the first time in Klarisky, where at the same time the memorial met Blaho Uhlár in person. The actors brought their own stories into their speeches, and often they played naked and barefoot. At the same time, he also worked in Západoslovenské vodárne, which means that he was not dependent on earnings from the theater, which was still not stable. After the conflict between Uhlár and Karásek, he decided to stay with Blaho, with whom, however, he did not get along at best when he left the theater. The intense time spent in the theater was one of the most beautiful for him and he is grateful that fate arranged a meeting of talented people. He has collaborated with people such as Jožo Chmel, Blaho Uhlár, Erika Lásková, Laco Kerata, Imro Maťo, Miloš Karásek, Zuza Piussi, Lucia Piussi and Inge Hrubaničová.