You will definitely be president, she told Václav Havel in 1989

Download image

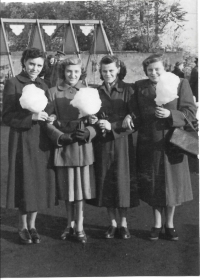

Hana Vrbicka was born on January 17, 1934 in Prague-Libni, she comes from four siblings. He has brothers Josef and Oldřich and a sister Boženka, who was partially paralyzed after polio in childhood. When she was five years old, the Second World War began, she experienced the period after the assassination of Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich and the bombing at the end of the war in 1945. Her aunt’s husband survived six years in the Dachau concentration camp, where he worked as an incinerator. She was eleven years old when Prague was liberated in 1945. Hana trained in Sokol, participated in the all-Sokol gathering in 1948, and then the organization was banned. She wanted to go to study to be able to teach in a kindergarten, but ended up working at the Brotherhood company. She and her husband Ctibor were married on June 13, 1953, their first son Pavel was born in the same year. She stayed on maternity leave for three years, meanwhile her husband left for the war. In 1965, the couple had a second son, Petr. Three years later, she graduated from the school of economics. She signed the Two Thousand Words statement. During the Velvet Revolution in 1989, she participated in demonstrations and marches through Prague.