The main principle was uncertainty and fear of trouble

Download image

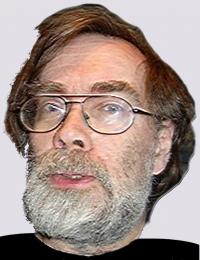

Josef Vlček was born on January 8, 1951 in Prague. He studied at the Nad Štolou secondary grammar school in a class focused on teaching English. A student summer job in Great Britain, during which he was able to purchase a large number of gramophone records with modern music, opened up a gate into the world of music for him. Josef then studied at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, specializing in the Czech language and history. However, due to his other interests, he did not complete his studies and he began working as a shop assistant and later as a purchaser in a secondhand bookshop. In 1971 he started his cooperation with the Jazz Section of the Union of Musicians, as part of which he published a number of various articles about current trends in music. He also participated in the organization of the Prague Jazz Days festival. From 1976 he was being summoned for interrogation to the State Security, in the mid-1980s he signed a commitment to secret cooperation as an agent with the pseudonym Tesák. The file with records of his cooperation with the State Security was shredded in December 1989. Josef Vlček states that the State Security asked him exclusively for information about the Jazz Section. For this reason, he gradually reduced his contacts with the Jazz section. In 1988, he became the editor of Melodie magazine. After November 1989, he was a co-founder of the Rock & Pop magazine. He also became a member of the team that established the first private radio station after 1989 - Radio Evropa 2. Since then, he worked as a founder or a consultant for many private radio stations in the Czech Republic. He has published a number of publications and articles on popular and alternative music and jazz.