I had to join the Hitlerjugend, but then they found that Mum was Jewish

Download image

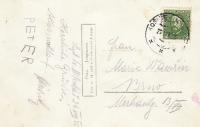

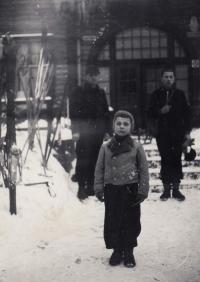

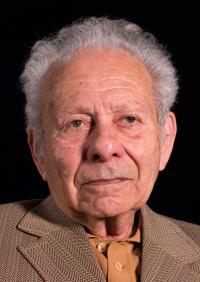

Petr Vavřín was born on 24 June 1929 in Brno into the family of Jindřich and Marie Vavřín. His mother was descended from the Löwenthals, a Jewish family of businessmen; his father’s ancestors were deep-rooted German inhabitants of Brno. His mother could not endure the pressure of the increasing persecution of Jews and committed suicide in 1939. His father married again a year later. His second wife Josefa was a Czech Austrian with German citizenship, and so Jindřich Vavřín was forced to become a German citizen as well. Petr Vavřín had to switch to a German grammar school and participate in Hitlerjugend activities for some time. At the age of 15 he found employment at a fabric dyeing plant. In 1945 he survived the bombing of Brno; he waited out the end of the war outside the city, in a shelter in Křtiny. In May 1945 his father and stepmother were interned in the camp in Maloměřice as part of the retaliatory anti-German repression; Brno citizens drove his German great-aunts out of the city in the so-called Pohořelice death march. Most of his Jewish relatives had died in concentration camps. After the war Petr Vavřín attended the Janáček Academy of Performing Arts and studied pedagogy. He taught music education for eight years at a teacher’s school in Boskovice and was then employed at the conservatoire in Kroměříž for the next 25 years. He drew his greatest joy from his daughter and his family life.