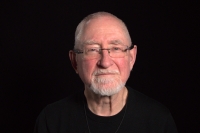

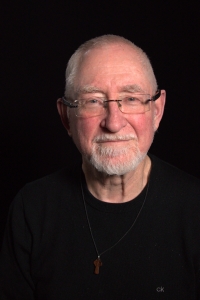

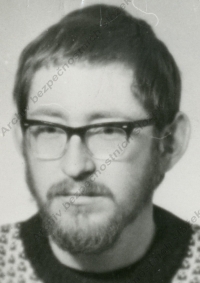

I was the eternal outsider

Download image

Gerald Turner was born in Sunbury on Thames near London on 8 September 1947. His parents, Grace and John, were ardent and convinced western communists. Gerald too - as early as 1965 - became a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain and later of a number of Communist and trade union organisations in the UK. After studying languages, he came to Prague in 1971 to work as a translator for the World Federation of Trade Unions, through which he travelled to many countries around the world. In the late 1970s he returned to London and began translating Czech literature, including authors such as Ludvík Vaculík, Milan Šimečka, Ivan Klíma and Václav Havel, for whom he was a personal translator in 2004-2011. In 1985-1990 he worked as the exclusive translator of the Czechoslovak Documentation Centre for Independent Literature. In 2022 he lived alternately in Prague and the UK.