The last visit to the imprisoned preacher. It wasn’t a dad, it was a skeleton

Download image

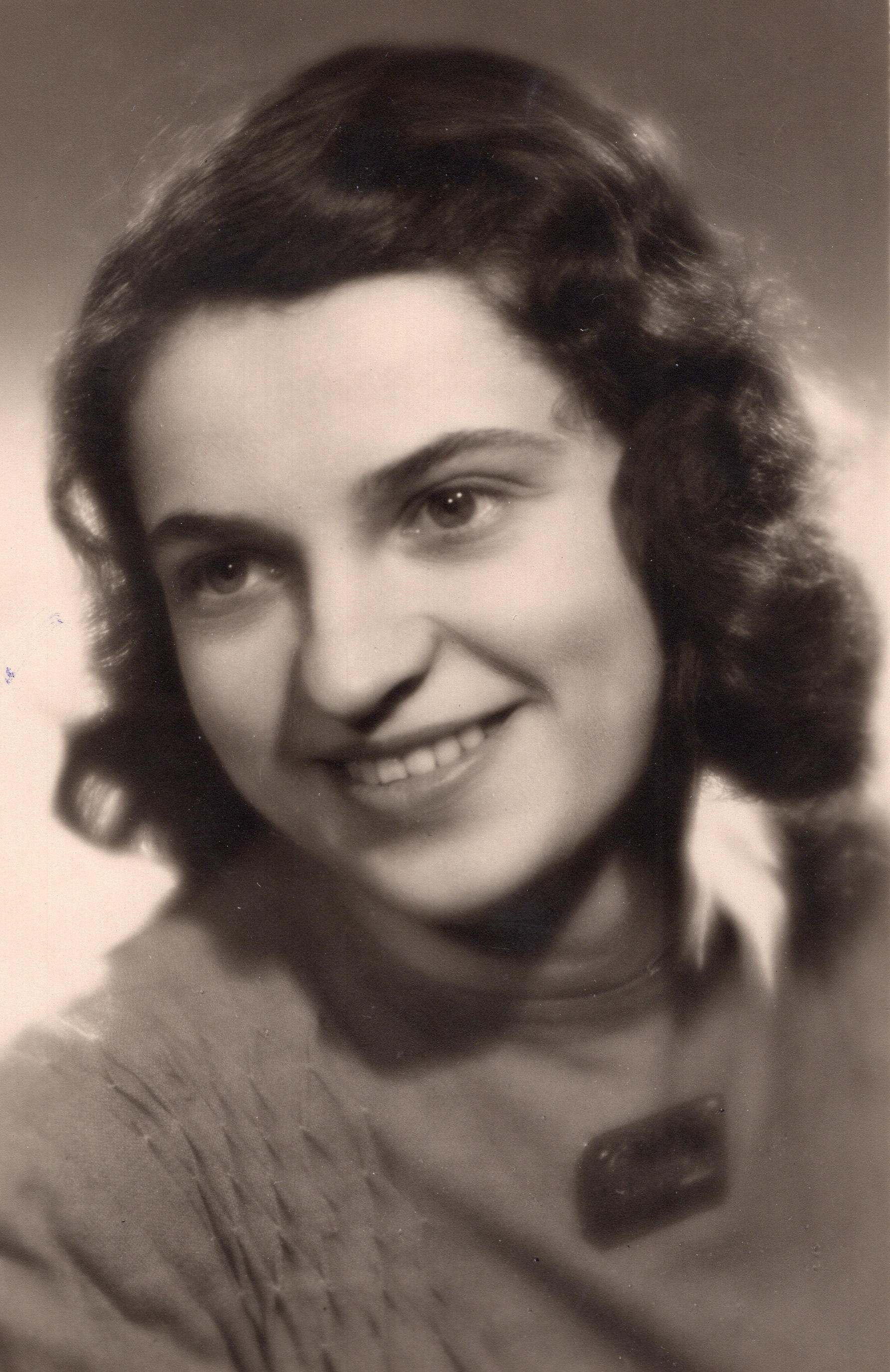

Věra Tučková, née Burgetová, was born on April 23, 1924 in the village Lipová in Prostějov district. She grew up in a large and strongly religious family. Her father, Cyril Burget, worked as a Baptist missionary in Vysoké Mýto, where thanks to him, the Baptist Christian congregation was established. He also managed to do this in 1929 in Kroměříž, where his family also moved and where the witness graduated from business school there. During World War II, the protectorate authorities totally deployed her to nearby Hulín, where she also lived through the dramatic end of the war. Cyril Burget actively participated in the anti-fascist resistance during the German occupation, first as a leader of an underground movement unit and from 1944 he commanded the partisan group Grado, with which he was to participate in the liberation of Kroměříž. In 1946, he became a spiritual preacher in the Baptist church in Vinohrady and later published a Czech Baptist magazine called Slova pro život (Words for life), which was later banned by the communist regime. He was immediately elected the secretary of the Fraternal Unity of Baptists in Czechoslovakia and briefly became its chairman. In June 1952, however, he was arrested by State Security and after a year spent in pre-trial detention, he appeared in a Kangaroo court with representatives of the Baptist Church. The Communist judiciary sentenced Cyril Burget to seven years in prison, and he served his sentence in the Valdice prison, where a witness visited him at the beginning of 1954, just before his death. Cyril Burget died on February 4, 1954. According to the funeral service report, he was soon cremated and the last farewell took place under the strict supervision of the security authorities. The father’s sealed urn with ashes was never given to the family, which is why the witness and her sister believe that his body was buried in the closed prison cemetery in Valdice. In 2005, a ceremonial unveiling of a commemorative plaque took place in the courtyard of the prayer hall of the Baptist church in Vinohrady, Prague. The witness worked for many years as an accountant for emergency service and lived in Cheb at the time of filming (June 2022).