Warsaw, the city that rose from the dead

Download image

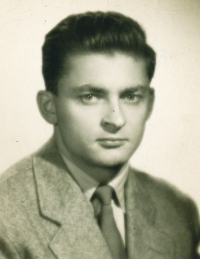

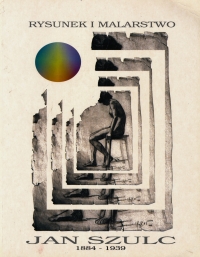

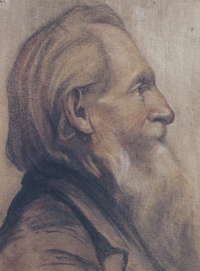

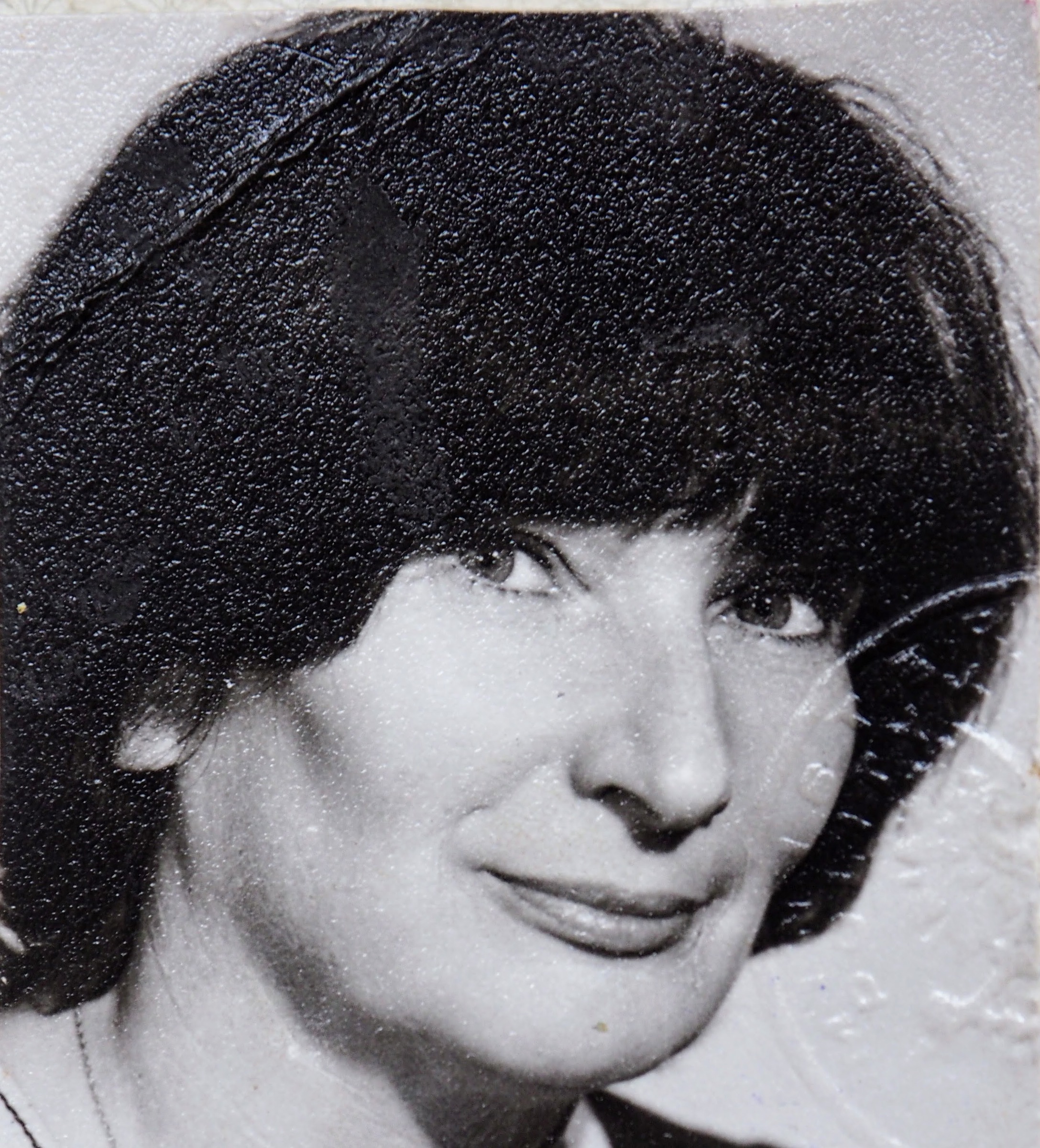

Bibiana Szulc was born on December 5th, 1932 as the last of seven daughters of Jan Szucl, a polish visual artist. After Poland had been invaded by Nazi Germany in 1939, four of her elder sisters joined the national resistance army (Armija Krajowa). Her father died in the first days of the war, being killed as a civil defence serviceman. Her mother with her three remaining daughters stayed in Warsaw. The uprising of August 1st, 1944 had been suppressed by the Germans, despite fierce resistance from the rebels; even when the fighting was still going on, the Germans started ‘depopulating’ the city. Mrs. Szulc and her three daughters departed for Auschwitz with the first transport on August 12th. In the camp, her two sisters were sent to a women’s camp, while Bibiana, being a twelve-years-old, stayed with her mother. Her older sisters were taken to work in the arms factory in Meuselwitz. She and her mother were transported to Berlin on January 17th, 1945, and were reportedly used as human shields and also as a workforce detailed to clean the streets of the city destroyed by bombing. During the last days of the war, a group of Poles, including Bibiana and her mother, embarked on a perilous journey back to Poland. After the war, Bibiana studied architecture and married her Czech colleague. She moved to Prague and got a job as an architect. In 1991, she joined the Association of Poles living in Czechoslovakia and has been working as its secretary.