In 1945, there was a man in the Strossmayer Square standing on a crate whipping the Germans. That was ugly...

Download image

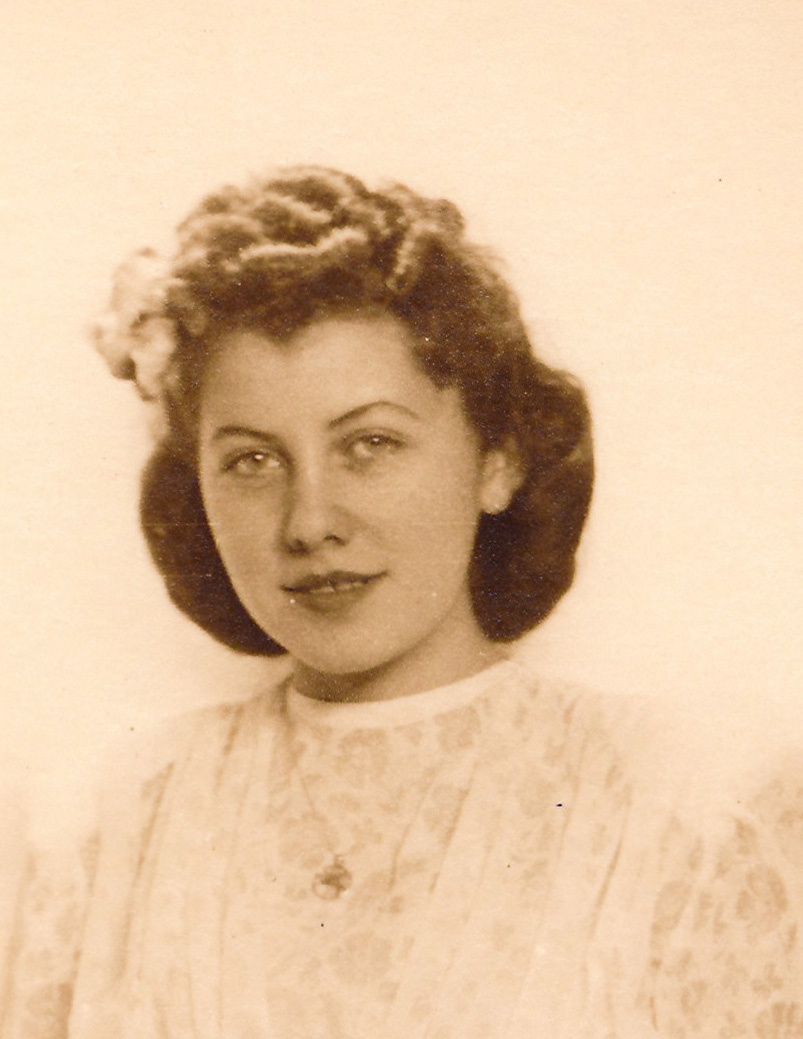

Zdeňka Svobodová née Štěpková was born on September 19th of 1926 in České Budějovice. Her father was a constructor who participated in several residential building projects in Praha´s luxury district of Hanspaulka. Her family moved between České Budějovice and Praha. As Zdeňka started primary school in Praha-Dejvice, her family had already settled in Praha permanently. During the economic crisis, her father strived to support the family. They moved to Letná near the Strossmayer Square. Zdeňka started attending gymnasium and in 1945 she graduated from secondary school. Because food rations were insufficient during the war, her parents would go to the Šumava foothills to get food as they knew local farmers. She recalls that they would come back with backpacks full of produce so the family would not starve. She also recalls quite a terrible experience, as she saw the German population being gathered in the Strossmayer Square after the liberation of Praha, swastikas being painted on their clothes and people being whipped. Inspired by her boyfriend, she decided to study medicine but after two years she found out that she was not suited to be a physician. She started to study at the Faculty of Education, where she devoted herself to drawing, an activity she always loved. She repeatedly tried to pass the entrance exams so she could study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Praha. The atmosphere of excitement of the second half of the 40s reached the highest point for her as she joined the march to Pražský hrad (Prague Castle) in February 1948. She passed the ‘ideological clearance’ that followed the coup and was allowed to graduate. In 1951, she married and soon gave birth to her first son. However, she had to manage the household by herself as her husband had to do the two-year compulsory military service. She speaks about how her father was tortured in detention after he had been arrested twice, as he was accused that he helped someone to cross the border illegally and that he insulted president Klement Gottwald. She also speaks about her experience with people impoverished by the 1953 financial reform. Since the 60s, Zdeňka had been working at the Výstavnictví Enterprise in Letná, where she had been drawing and colouring the exhibition plans.