I have nice memories of Romania, but I have had a good life everywhere

Download image

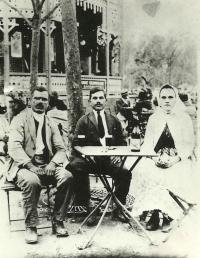

Anna Šubová was born March 24, 1936 in the Slovak village Termezov in the territory of present-day Romania. She spent her entire childhood among Romanian Slovaks who had begun to settle the area at the end of the 18th century. Since she was a little girl she has had to help on their small farm, which was basically the only source of the family’s livelihood. Urged by their eldest sons, shortly after the war Anna’s parents decided to accept the offer of the Czechoslovak authorities to relocate and settle in the borderland areas. The family left Romania at the end of 1947 and they settled in the village Meziříčí in the Český Krumlov region, but after a short time they moved from there to the village Desky. Both villages, just like the surrounding area, were settled by Slovaks from Romania. They formed a specific closed ethnic community which maintained lifestyle to similar that in Romania. However, Anna Šubová was in the first generation that established contacts with the neighbouring Czech inhabitants and she significantly contributed to the assimilation of the Slovak minority. In 1953 she married her neighbour Jan Šuba, and together they moved to nearby Ličov, later to the Třebíč region and in the early 1970s they moved to Dolní Dunajovice in southern Moravia. She has never broken her ties to her fellow countrymen and she still keeps in touch with her relatives in Romania.