Be grateful we have such a beautiful country, and fight to make sure we never know war again

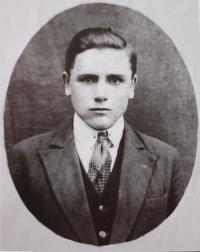

Alexandr Stejskal was born on 10 April 1945 in the Czech village of Sofievka in Volhynia, which is now a part of Ukraine. Alexandr’s grandfather Josef Stejskal had immigrated to Volhynia with his family after the end of the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, when Czech lands were rife with poverty and tsarist Russia had cheap land for sale. The Volhynian Czechs persevered through hard times, built up houses, schools, churches, culture houses; they ploughed fields and soon began to thrive. Alexandr’s grandfather and other relatives fought as Czechoslovak legionaries in World War I, and Alexandr’s father and uncles took part in the fighting of World War II, including the Battle of Moscow, the tank battles at Kursk, or the Battle of Kiev. Alexandr and his family returned to Czechoslovakia in 1947 and settled down in Broumov, in an area emptied by the deportation of Sudeten Germans. He regularly returns to Volhynia to honour the memory of his ancestors, and he is a member of the Association of Czech from Volhynia and Their Friends. He still lives in Broumov, where he worked for many years as a fireman and where he and his wife Olga raised two daughters.