When my mother disappeared in the transport, I was left alone and homeless in Prague

Download image

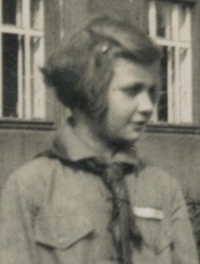

Mgr. Dagmar Stará, née Pirchanová, was born on February 27, 1928 in Prague. Her mother Hilda Löwová (also spelled Loevová or Lévová) was of Jewish origin, her father Augustin Pirchan was a physician, an internist specializing in radiotherapy. Her parents married in 1926 after an eleven-year relationship. They divorced after Dagmar was born, and her father remarried and died when she was six years old. The witness grew up with her mother and grandfather Otakar Pirchan, a government councillor who had a strong educational influence on her. After the establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in 1939, anti-Jewish measures began to apply to the Jewish part of the family. Her grandfather died in 1941, her aunt Markéta Freund and other relatives were deported in 1942. Mother Hilda was sent to the transport by the Nazis soon after Dagmar reached the age of fifteen, in March 1943. After the sudden death of her housekeeper, Dagmar found herself alone in Prague. In the meantime, she was expelled from the gymnasium as a first-grade mixed-race girl. She took refuge with her aunt Ludmila in Písek, where she spent the next five years. Because she was expelled from the grammar school as a first grade mixed-race girl and was not allowed to attend any schools, she worked in a factory in Písek. None of the family returned after the war, only a distant cousin, Karel Schick, survived and his parents sent him to England in 1939. After the war, the witness returned to her studies, graduated from high school and in 1948 graduated. The same year she married pharmacist František Starý and they moved to Prague. She graduated from the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, majoring in art history and classical archaeology. During her studies, her first daughter was born. In 1961 she joined the National Museum, where she worked for more than three decades as a historian in the department of historical archaeology. In 1957, when she was about to work externally with the travel agency Čedok, State Security Service (StB) used her wartime trauma to manipulate her into working with them. She left the National Museum in 1992, but continued to work as an expert expert and specialist until she was eighty-five. Her daughter Eva, a restorer, suffered from health problems from birth and Dagmar still cares for her at the advanced age of seventy-seven. She divorced in the first half of the sixties and raised two daughters.