Not the success of an action counts, but the action itself

Download image

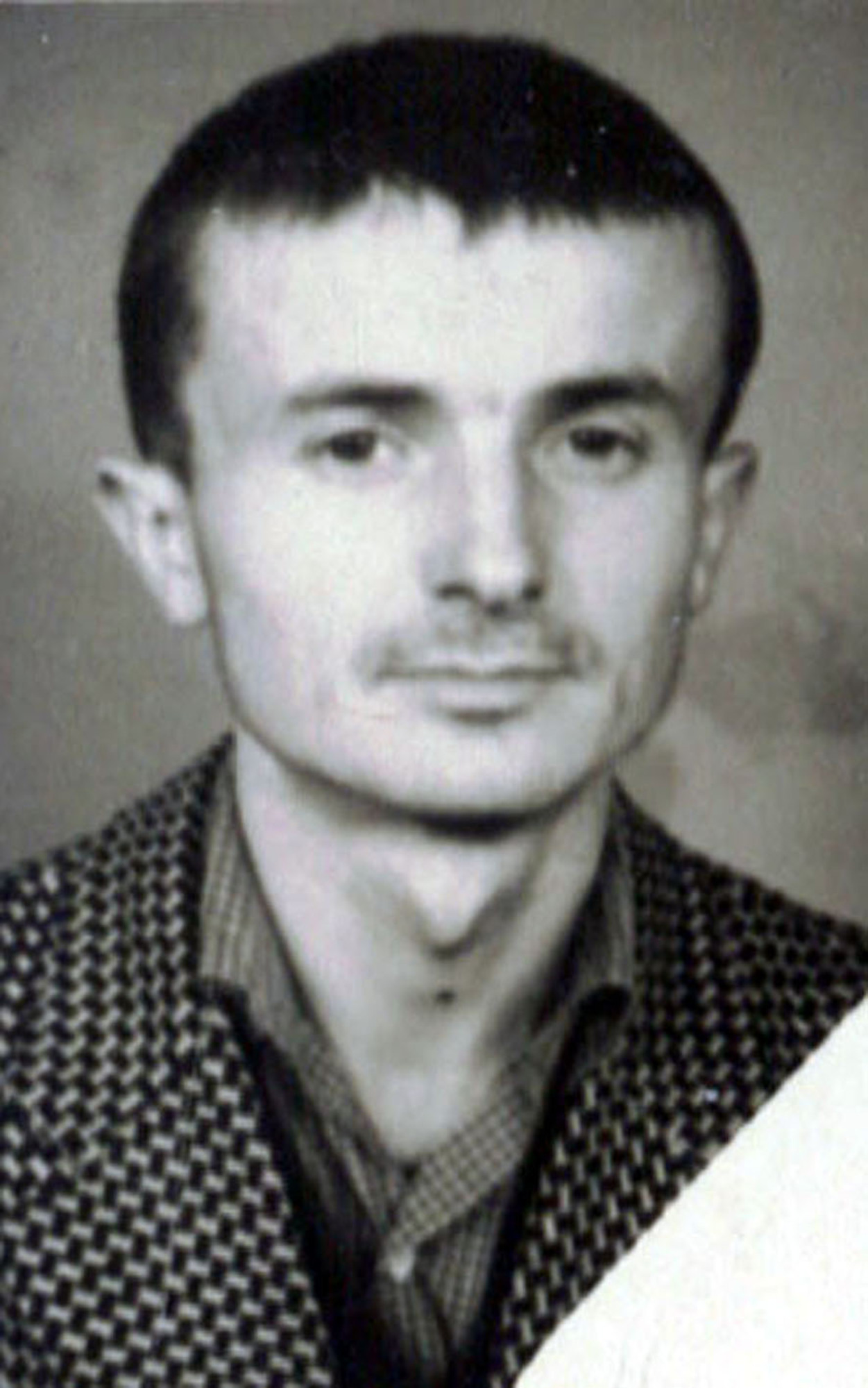

Born on 26 March 1933 in Coroi commune, Arad county, a student at the Polytechnic in Timișoara, one of the leaders of the student movements of October 1956 For the communist bloc, the year 1956 meant the Hungarian Revolution, liquidated by the brutal intervention of Soviet troops. Echoes of this anti-communist movement were felt throughout Eastern Europe. In Romania there was an immediate reaction on the part of students. In October and November 1956 there were protest movements in a number of university centres, the most organised student movement being in Timișoara. Between 23 and 26 October 1956, students from Timișoara were up to date with what was happening in the neighbouring country and with the involvement of their counterparts in the movement via foreign radio stations, including Hungarian and Yugoslav stations. On 28-29 October, the students of the Mechanics Faculty set up an initiative group to organise and co-ordinate protest actions. The organisers included Aurel Baghiu, Caius Muţiu, Teodor Stanca, Frederich Bart, Ladislau Nagy, Valentin Rusu, and Heinrich Drobny. At two p.m. on 30 October they called a large meeting of students from the whole of Timișoara. The rector of the Polytechnic Institute, the deans of the faculties and the deputy minister of education, in Timișoara at the time, were invited to the meeting on 30 October, attended by around two thousand students. During the meeting the students voiced their dissatisfaction with the situation in Romania and shouted anti-Soviet slogans. Likewise, they presented a set of demands, containing twelve points. Despite the fact that the Party representatives promised that they would bring the students’ demands to the attention of the leadership and that nobody would suffer reprisals for the meeting, shortly thereafter the arrests began. Among those arrested was Teodor Stanca. He was sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment for “public agitation”. After seven years in various prisons (Timișoara, Gherla and the penal colonies of Salcia, Giurgeni and Periprava), he was released on 3 February 1963, following an amnesty decree. After 1989 he became a member of Romania’s parliament, representing the National Christian Democrat Peasants’ Party (1996-2000) and has been a leading member of the Romanian Association of Former Political Prisoners. He lives in Timişoara.