Justice, freedom and joy

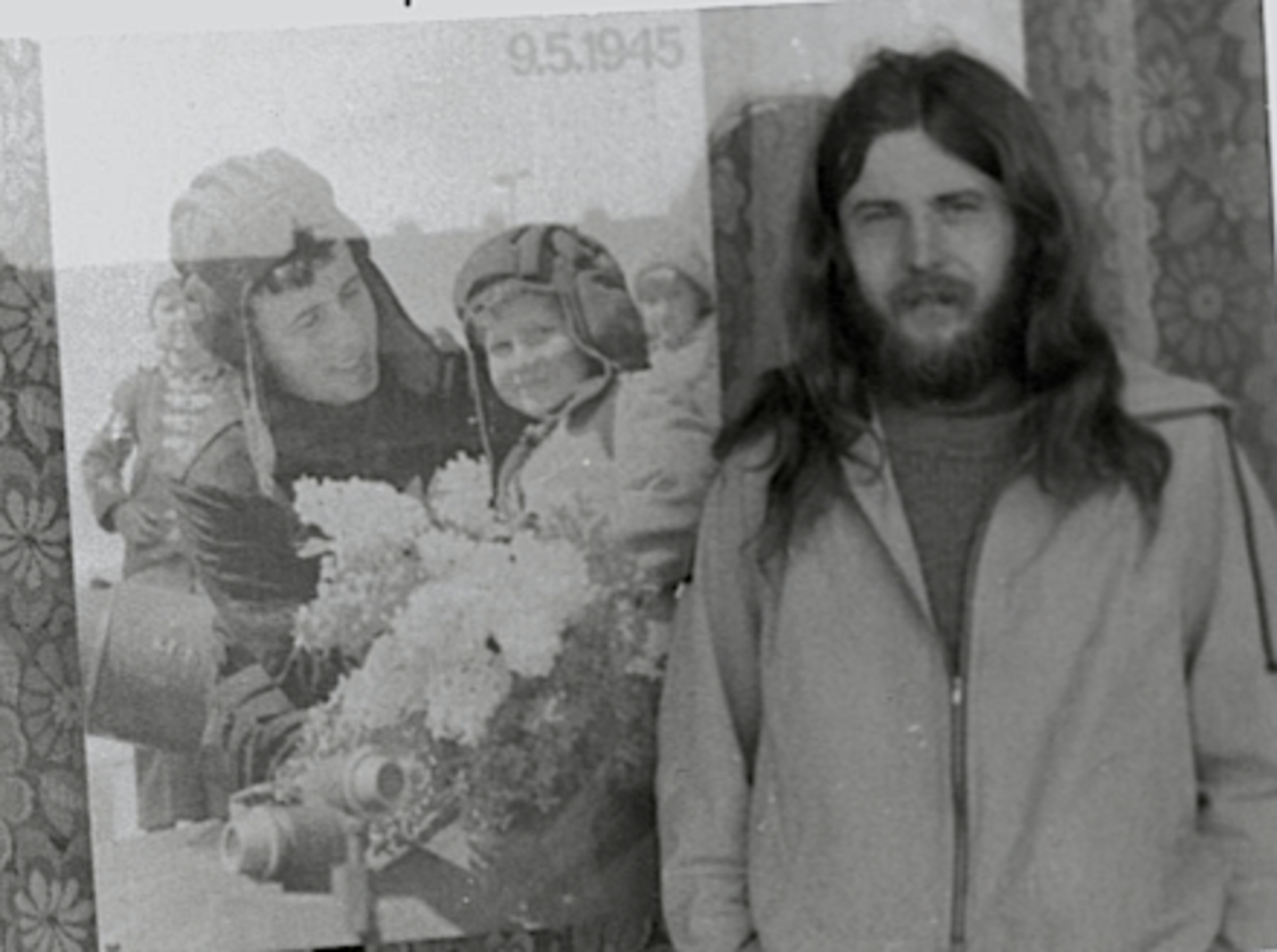

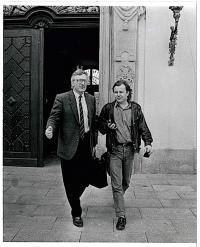

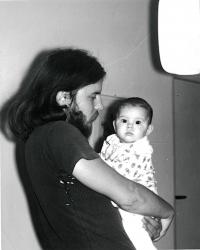

Jaroslav Spurný was born on 14 July, 1955 in Kyjov. He was a talented student but soon he got into conflict with the regime due to his long hair and free minded opinions. On 1st September, 1975 he finished studying the secondary engineering school and his decision he explained in a letter, where he expressed his opinions to breaching basic human rights. In order not to have to start the basic military service he committed a demonstrative suicide. The other months he spent in a psychiatric hospital in Kroměříž. Later he returned there about six times - the hospital served as a shelter and a protection against charges of parasitism. Eventually he didn’t avoid it though. In January 1976 the secret police charged him with parasitism and he was charged with half a year to serve in prison suspended for two years. In 1976 he was arrested again. He spent five and half months in custody in Brno. In 1978 he moved together with his wife Kateřina to Zlín (former Gottwaldov), where two daughters were born. He got engaged in activities of Zlín dissident group. On his typewriter he re-typed the forbidden books and enlarged the cyclostyle issues of Infoch and VONS reports. In 1983 the family moved to Prague. Jaroslav signed the Chart 77 and further he participated in dissent activities. He was a part of the Independent Press Centre establishment, and later he became a member of the editorial office Information service, which got transformer into the weekly Respekt. For his work he was awarded a journalist awards of Karel Havlíček Borovský and Ferdinand Peroutka.