It’s good that they didn’t appropriate my father like they did Fučík

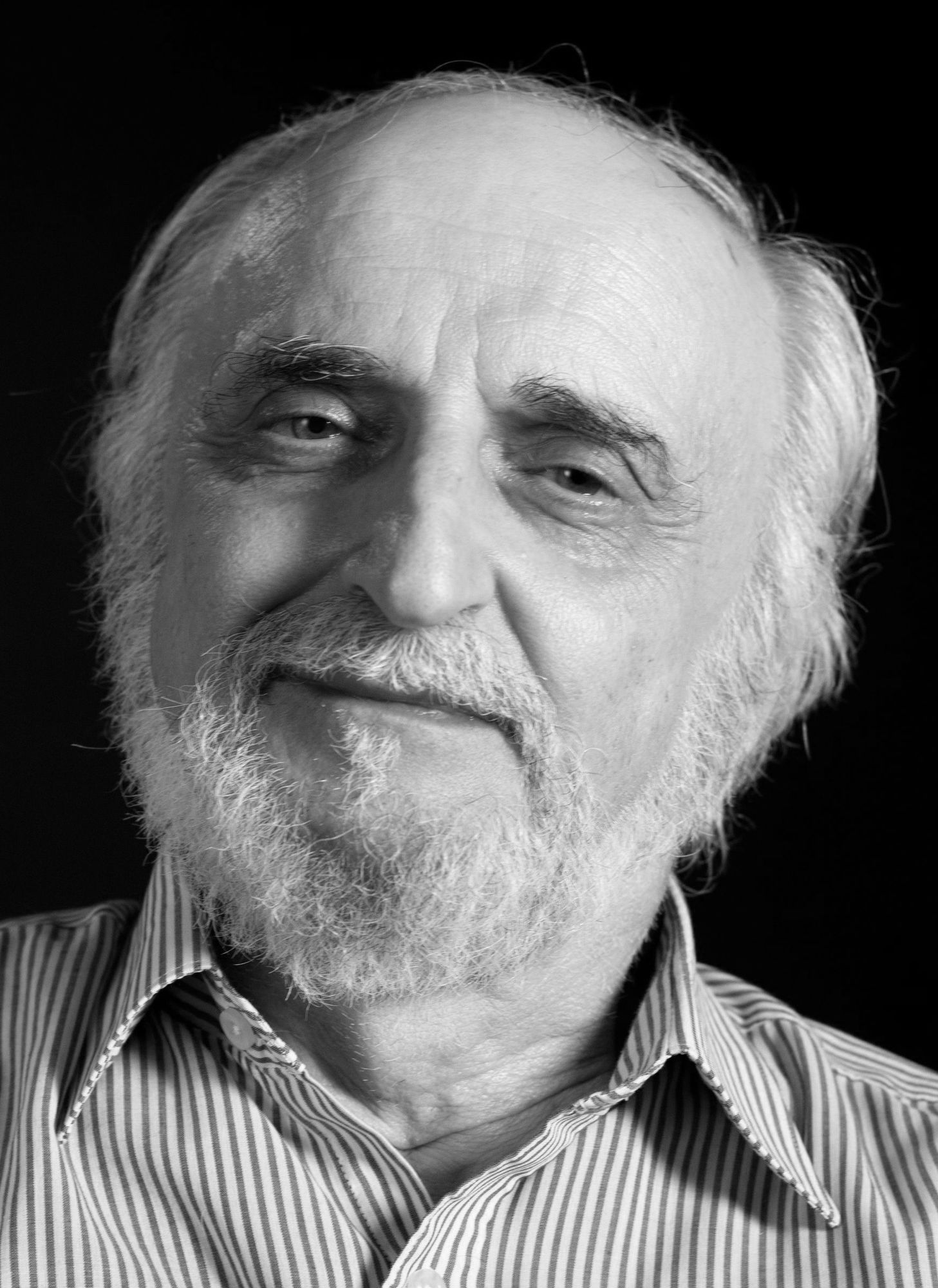

Ing. Tomáš Sousedík was born on 10 October 1943 in Vsetín. He comes from the family of a Vsetín businessman who was the most important employer in Vsetín and the surrounding area in the interwar years and whose technical erudition and visionary approach to electrical engineering greatly surpassed the borders of Czechoslovakia. When World War II broke out and Czechoslovakia was occupied by the Nazis, Josef Sousedík had to leave the Ringhoffer-Tatra factory, which he had directed. He devoted himself fully to the resistance movement. His son Tomáš was less than a year old when his father was shot during an interrogation by the Gestapo - he had attempted to escape. Despite his father’s merits, his family was harshly punished after the war. Tomáš himself was fortunate enough to graduate from the University of Economics; he also made a name for himself as a football player. For some time he worked as an economist-planner at ČKD, after 1968 he moved on to less exposed gallery jobs. Starting in 1978, he was intendant of Karlín Music Theatre twelve times, and after November 1989 he became the last managing director of the Pragokoncert agency. From the mid-1990s he took up his own business in the field of concert management. His lifelong hobby is professional-level pigeon keeping. He also strives to reawaken and rehabilitate the memory of his father, Josef Sousedík.